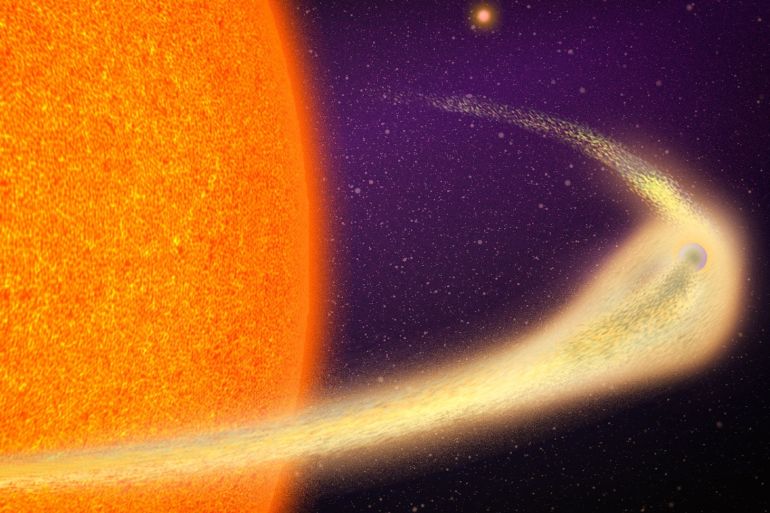

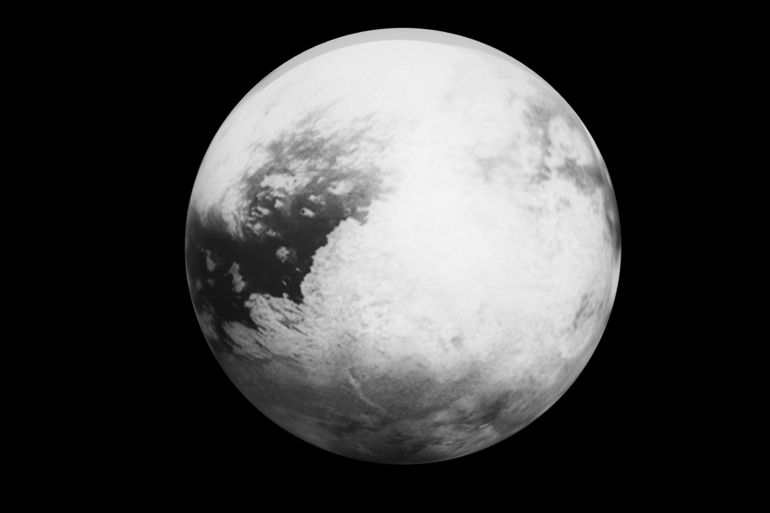

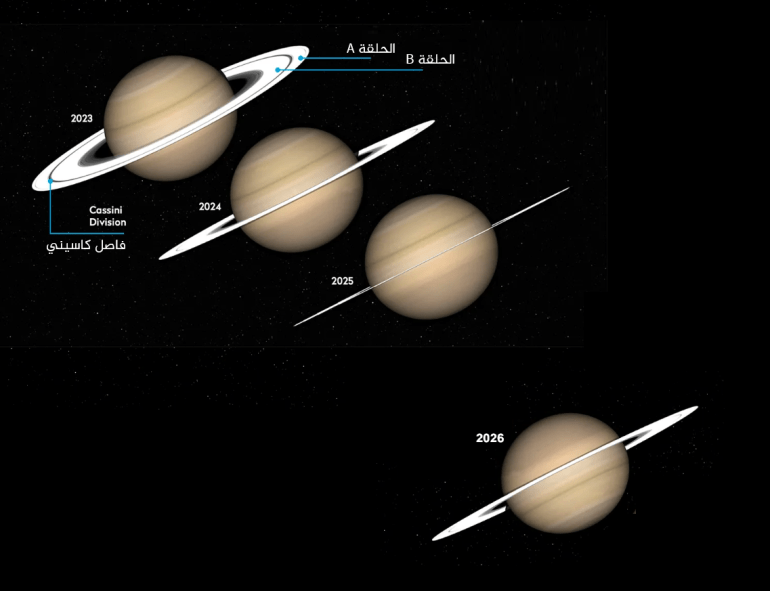

Saturn is one of the most beautiful and impressive planets in the solar system; many even consider it the most beautiful of all, thanks to its majestic rings that have captivated human eyes for hundreds of years. These rings, which seemed to almost disappear from Earth’s view in 2025, are returning to shine and become clearer starting in January 2026, in an astronomical event eagerly awaited by enthusiasts and scientists alike.

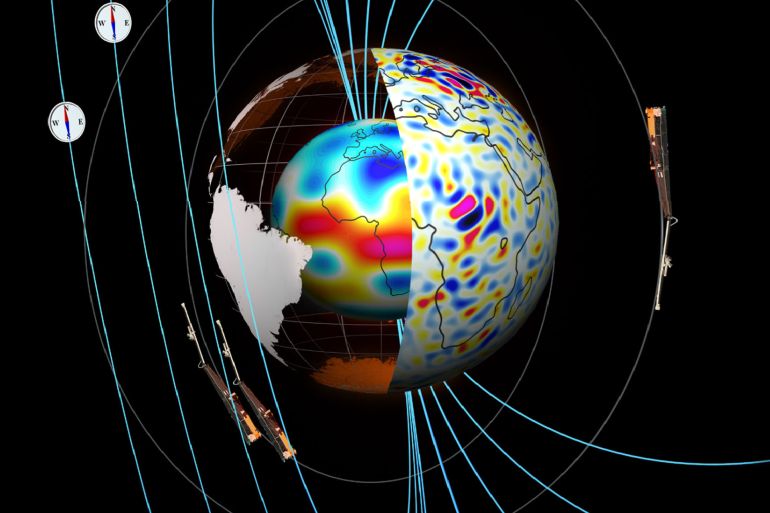

The disappearance of Saturn’s rings is not a real event, but rather an astronomical optical illusion known as a Ring-Plane Crossing. This occurs when Saturn’s rings are positioned exactly edge-on relative to Earth, so we see them from the side, not from above.

Saturn’s axis of rotation is tilted by about 27 degrees. As it orbits the Sun, which takes about 29.5 Earth years, our viewing angle of the rings changes. Approximately every 13.7 to 15.7 years, the rings align in a straight line with Earth, appearing as a thin line that is almost invisible.

In 2025, this phenomenon peaked twice: first in March 2025 when the rings appeared exactly edge-on, and again when they reached a second narrow point in late November 2025.

Since the thickness of the rings does not exceed 10 meters, viewing them from the side makes them almost invisible, even through most telescopes.

From “Ears” to the Precision of Modern Telescopes

In the 17th century, an Italian scientist described the planet Saturn as having “ears,” referring to what he saw through his primitive instruments. Despite the limited visibility at the time, he realized there was something unusual surrounding this planet.

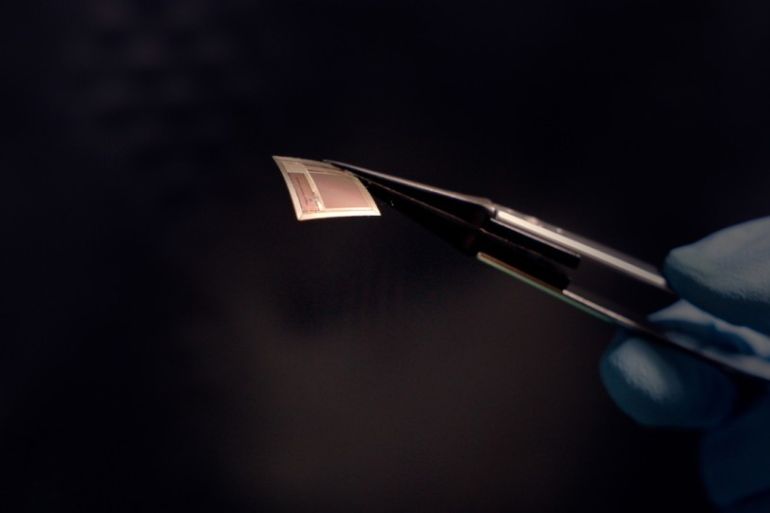

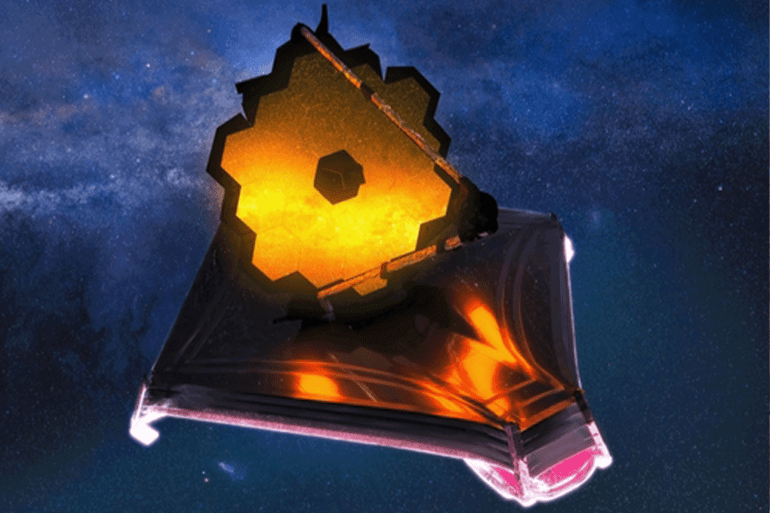

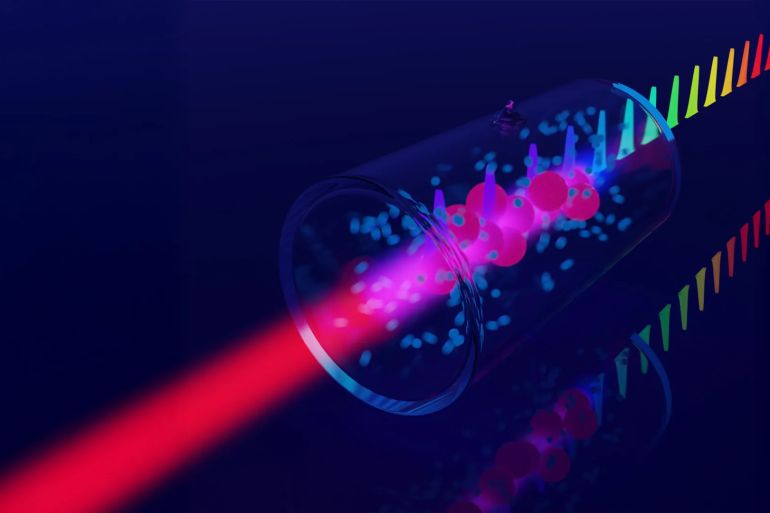

Today, modern telescopes and space observatories reveal that these “ears” are nothing but millions of particles of ice and rock, orbiting Saturn in wide arcs known as rings. They are not just cosmic decoration but represent a natural laboratory for understanding gravitational forces and the motion of objects in space.

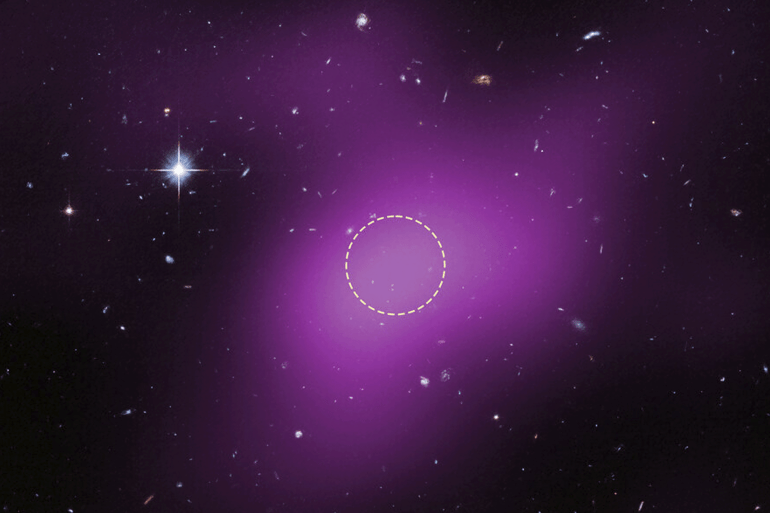

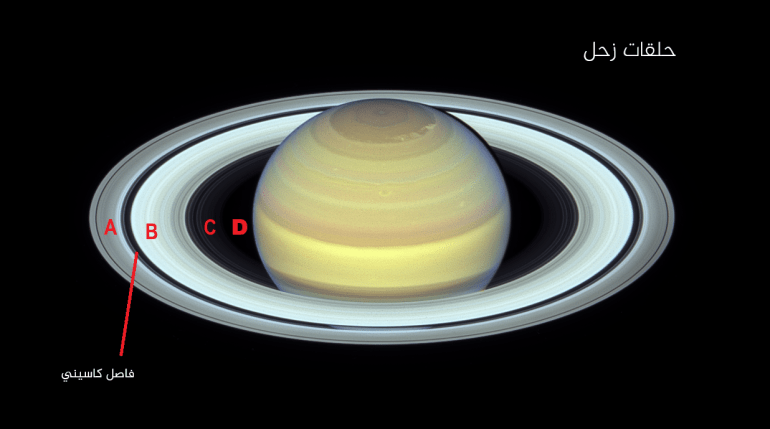

Saturn’s main rings are divided into seven rings designated by letters of the English alphabet. Between the first and second rings lies a famous gap called the Cassini Division, which is about 4,800 kilometers wide.

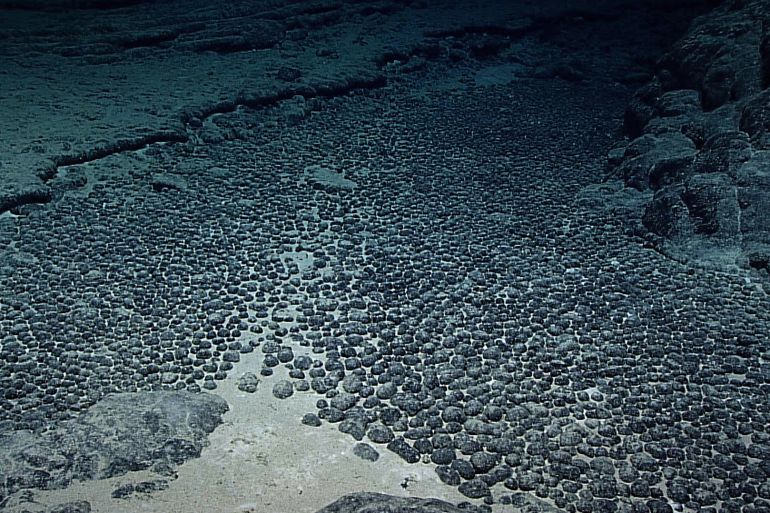

These gaps form due to gravitational interactions and orbital motions that clear some paths of particles. The rings themselves are not solid sheets but consist of pieces ranging in size from dust grains to chunks the size of buses.

The Fast Giant

Saturn orbits the Sun in a nearly circular path at an average distance of about 9.5 astronomical units, which is about nine and a half times farther than Earth. It takes about 29.5 Earth years to complete one orbit around the Sun, known as a “Saturnian” year.

Despite its enormous size, Saturn rotates rapidly on its axis, completing one rotation in just about 10 hours and 33 minutes. This rapid rotation causes the planet to flatten at the poles and bulge noticeably at the equator, with gravitational effects that help stabilize the ring system. However, this rotation does not affect the appearance of the rings from Earth; the most important factor is the tilt of the planet’s axis.

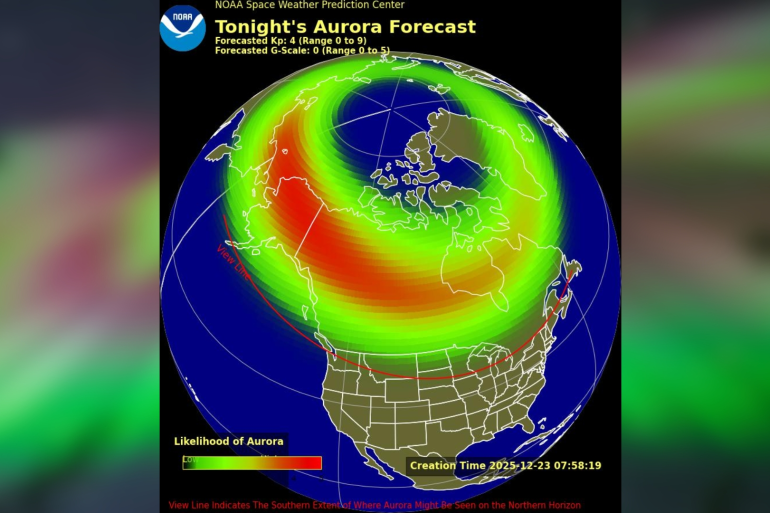

Saturn has an axial tilt of 26.7 degrees, an angle very close to Earth’s axial tilt of 23.5 degrees. Just as Earth’s axial tilt causes the succession of the four seasons, Saturn’s axial tilt leads to what could be called Saturnian seasons, during which the angle of illumination and visibility of the rings changes.

Since Earth itself is a tilted planet and orbits the Sun on a different path, the mutual perspective between Earth and Saturn constantly changes. Sometimes we are above the plane of Saturn’s rings and see them wide and bright; other times we pass almost through the plane of the rings themselves, making them appear as a thin