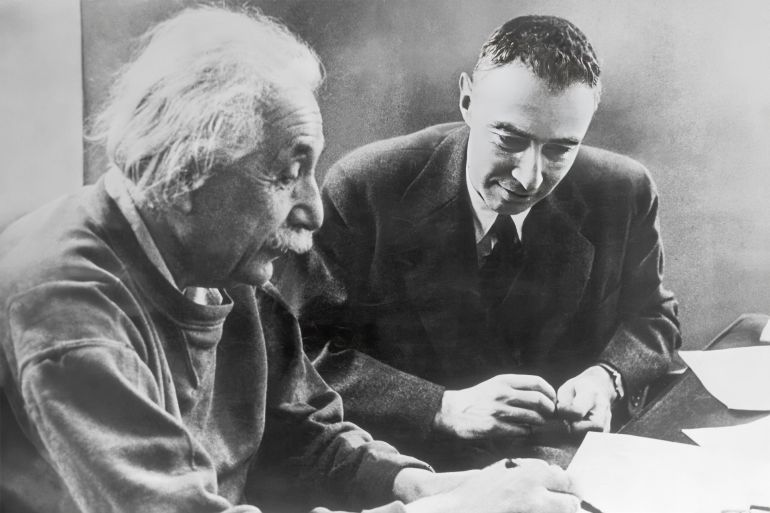

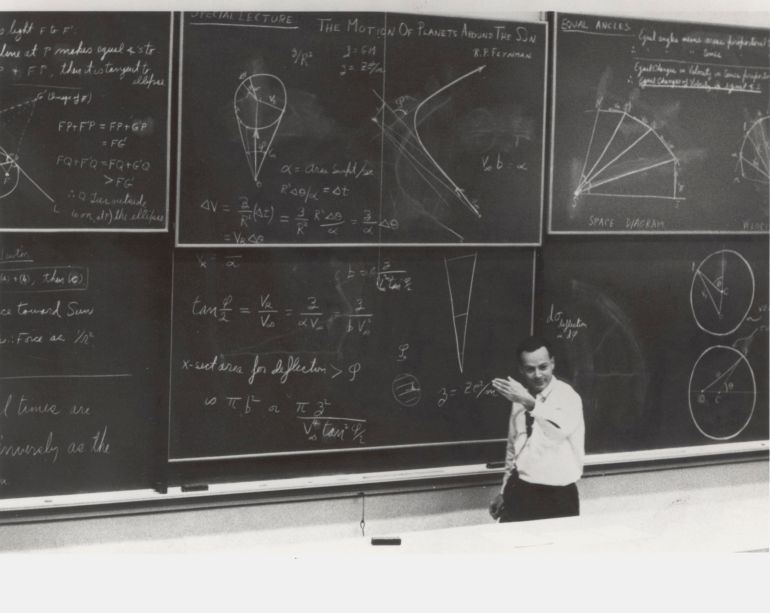

Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman once said, “The philosophy of science is as useful to scientists as ornithology is to birds.”

This quote is often used to mock the philosophy of science, but a deeper reflection reveals another side. Feynman viewed scientists as “craftspeople,” engaged in a precise and very important craft that demands all their time.

From this perspective, they are not expected to work or offer opinions outside their field of expertise; therefore, he also said, “A scientist who talks about things outside of science is as much a fool as the person sitting next to him.”

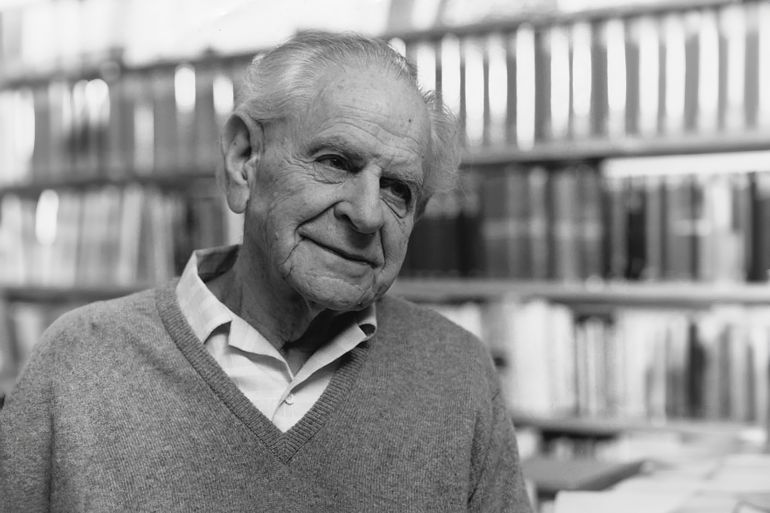

What Thomas Kuhn Says

However, the matter may be deeper than that. In his book “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,” Thomas Kuhn points out that during periods of “crisis”—when scientists in a given field face problems unsolvable within the prevailing framework—they naturally tend toward philosophy. This opens the door to questioning and discussing new, non-intuitive ideas, potentially helping them think “outside the box” and break the constraints of the prevailing paradigm.

Kuhn believed that science does not always progress in a straight line of quiet accumulation but often goes through cycles. It begins with a phase of “normal science,” where researchers work within an agreed-upon paradigm—a set of assumptions, tools, standards, and successful examples that define acceptable scientific questions and how answers are measured.

In this climate, the goal of scientists is usually not to question the foundations but to solve specific “puzzles,” such as improving measurements, expanding applications, and filling gaps within the prevailing framework.

But over time, anomalies or exceptions appear—results that do not easily fit the model, or recurring problems that remain unsolved despite increasing technical skill.

Initially, these anomalies are treated as experimental noise, equipment deficiencies, sampling errors, or mere details to be resolved later. However, their accumulation creates what Kuhn calls a “crisis”—a moment when the framework itself begins to lose its ability to guide research. Confidence in the rules of the game is shaken, and the question becomes: Is the problem in the data, or in the way we understand the data?

It is precisely here that scientists lean toward philosophy in a very practical sense, returning to questions that the paradigm had obscured or made seem obvious: What concepts are we fundamentally relying on? What are our definitions of the phenomenon? What are the underlying assumptions in our tools and language? What do we consider an acceptable explanation? What are the standards of “proof,” “causality,” and “measurement” in this field?

Thus, philosophy allows for a kind of cognitive breathing room—an expansion of the space of the possible.

A Supporting Role

Philosophy can indeed perform this role skillfully. Some naturalist philosophers even expand the scope of philosophy’s role in aiding science to include refining concepts and clarifying definitions, precisely determining the meanings of terms like causality, natural law, explanation, probability, randomness, and complexity.

This is important because many scientific disputes arise from conceptual ambiguity, not a lack of data.

In this context, philosophy provides science with tools to clarify the logic of reasoning and methods of proof, such as induction, deduction, “inference to the best explanation,” and the role of models and auxiliary hypotheses.

Philosophy of science also acts as a kind of “methodological diagnosis,” asking: How is a theory constructed? When do we consider it supported? Does a crucial experiment truly exist? In doing so, it highlights the limits of