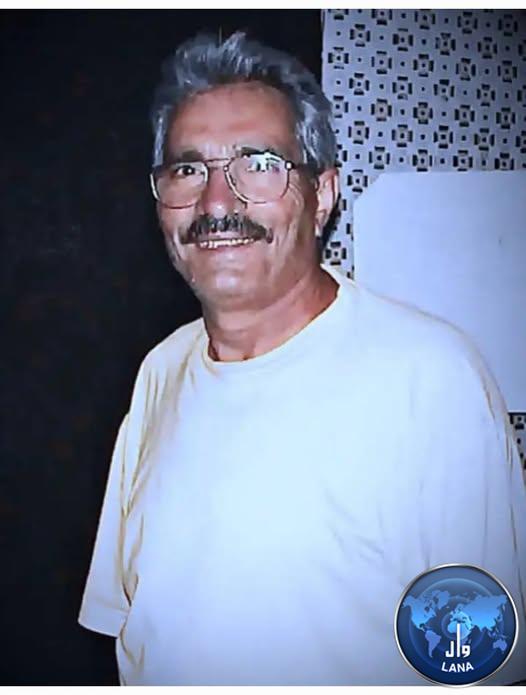

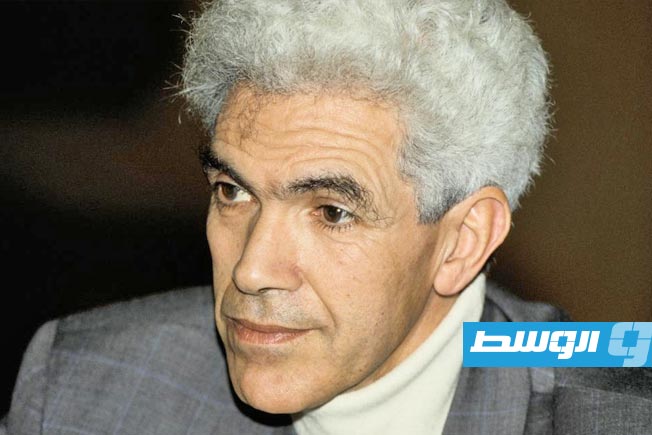

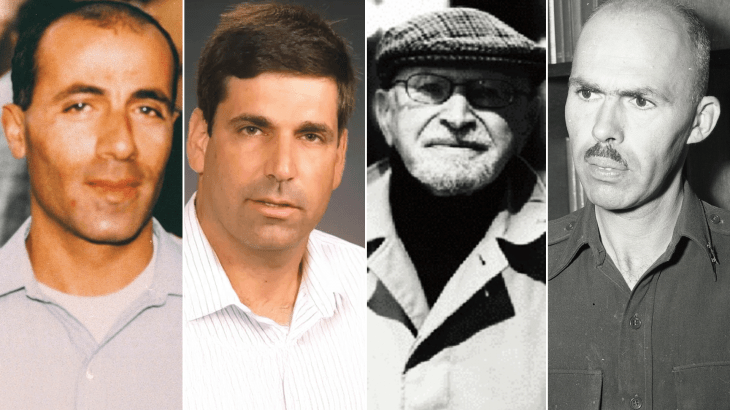

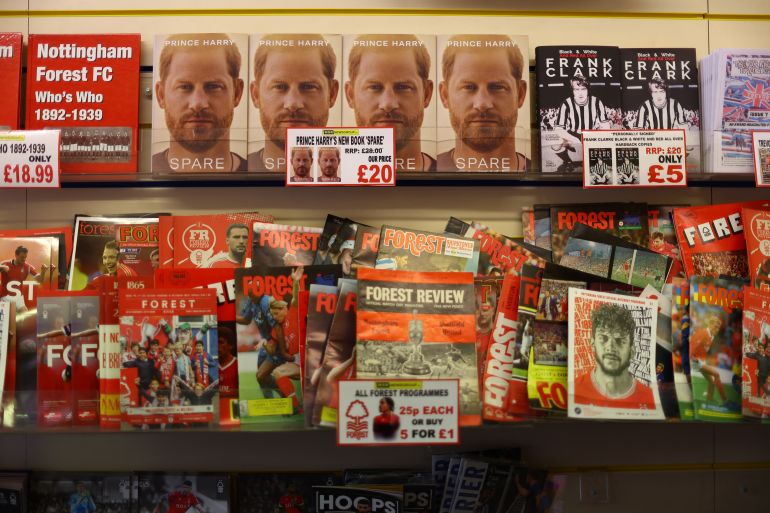

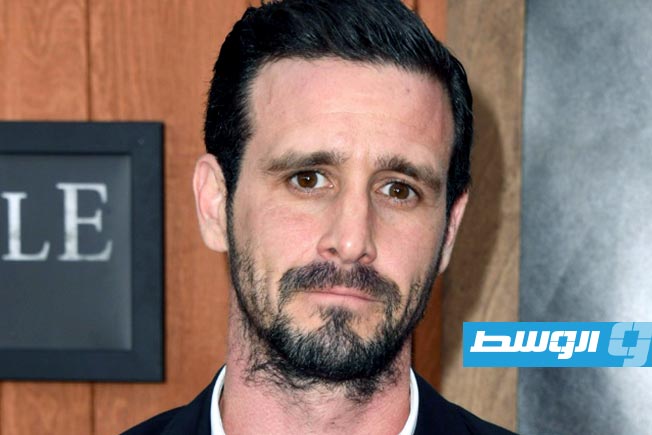

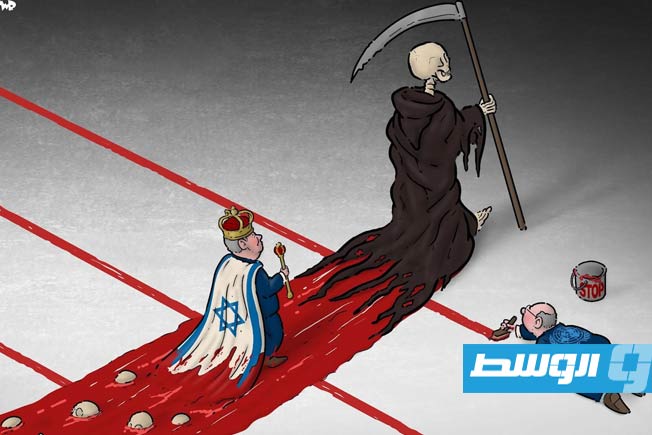

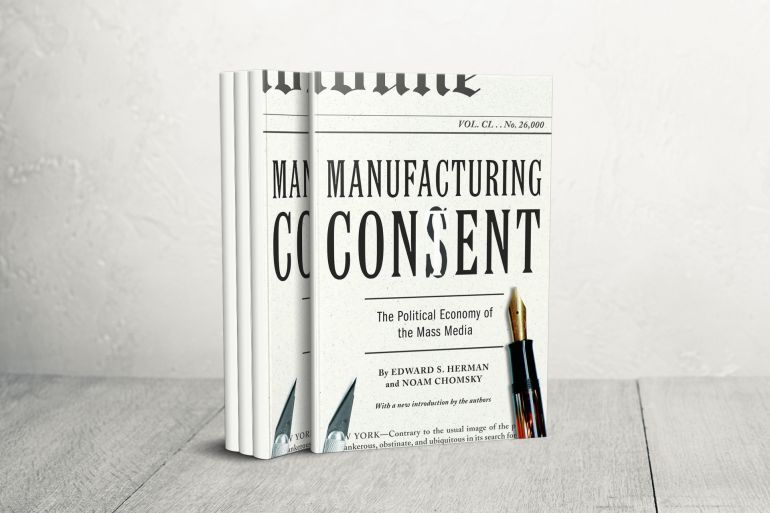

Finally, an image has surfaced that is difficult to imagine easily: the great critical intellectual sitting in a private, quiet, informal space with Jeffrey Epstein. The image is not scandalous in form, nor does it carry any direct criminal implication, but on a symbolic level, it is shocking. It brings together a radical intellectual who for decades represented the voice of radical critique against power, and a convicted man whose name has become synonymous with dark networks of influence and moral corruption.

The photo did not come alone. In December of this year, a new batch of documents, photos, and records related to the Epstein case was released, as part of a long legal and media process that reopened the network of his connections with politicians, academics, and wealthy businessmen.

Among those materials, Chomsky’s name is no longer a passing or marginal mention, but is now confirmed within a record of repeated meetings, some of which occurred after Epstein’s first conviction in 2008.

This is precisely where the shock occurred. Not because the meeting itself is a crime, nor because the photo reveals anything legally prohibited, but because the public’s critical imagination could not accommodate this scene. Here is a thinker who built his fame on deconstructing the relationship between money, power, and media, appearing within a social circle he himself had repeatedly described as the “kitchens of hegemony.”

How did the story begin?

In the summer of 2023, as the U.S. Justice Department was reopening the files of Jeffrey Epstein, convicted of sex crimes, following the disclosure of documents and records related to his vast network of connections with politicians, academics, and businessmen, an unexpected name appeared in the records: Noam Chomsky, one of the most influential critical intellectuals in the contemporary world.

It was not a sensational journalistic leak, nor a criminal accusation. What was simply revealed was that Chomsky met Epstein several times after his first conviction in 2008 for sexually assaulting minors, and that these meetings included discussions described as academic and intellectual, covering—according to what was announced—global politics, media, and possibly issues related to research funding or institutional coordination.

The shock did not stem from the meeting itself alone, but from the symbolic contradiction. How could a thinker who dedicated his life to deconstructing networks of power and money, and to analyzing the complicity between political and economic elites, sit—even under the title of an “intellectual discussion”—with a figure who has become a symbol of moral corruption and dark influence?

When questions were directed at Chomsky, his initial response was sharp and brief. He said the matter was a “private affair” and not the public’s business, that the meetings involved no legal violation and were unrelated to Epstein’s crimes, and that they were confined to the framework of intellectual discussions and nothing more. He also indicated that talking about these meetings involved unjustified curiosity and that focusing on them distracted attention from more important political issues.

This justification—in its tone and scope—did not close the debate but opened it. For many, the question was not legal, but cultural and ethical: Does the critical intellectual have the right to completely separate his ideas from the context of his relationships? Is it enough to say a meeting is “intellectual” when the other party is part of an influence network later used to whitewash reputations and build legitimacy?

Chomsky later provided a justification of a technical nature, explaining that his communication with Epstein concerned complex financial arrangements related to the assets of his late wife, Carol Chomsky. According to press reports, Chomsky indicated that the matter did not go beyond being a technical consultation for transferring private funds between his accounts, stressing that his relationship with Epstein was purely transactional.

However, for his critics, this justification remains insufficient, as it raises a fundamental question: Is the thinker who diss