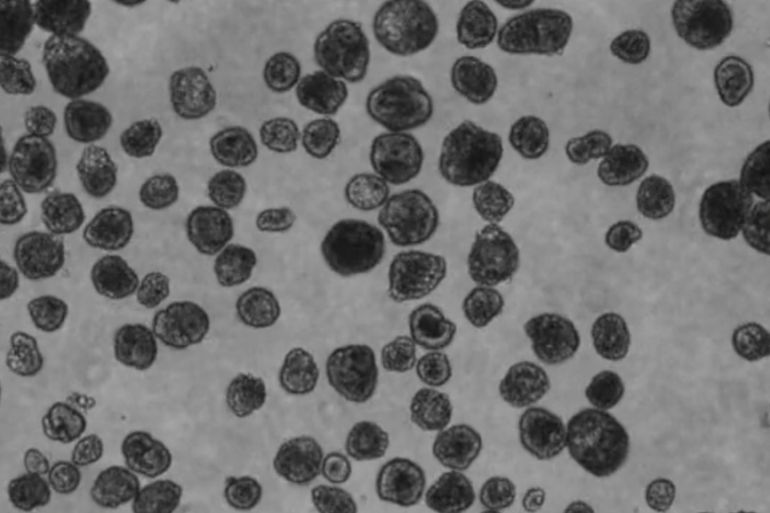

On the coasts of South Africa, in shallow pools whose salinity changes month by month and which are exposed to drought, heat, and cold, there are rock formations that to the eye appear as mere layered outcrops. In reality, however, they are “living systems” built by microscopic organisms since ancient times.

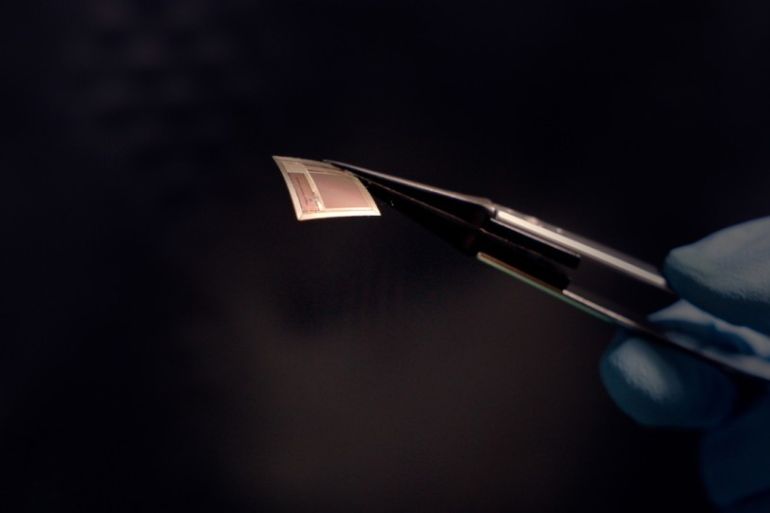

These amazing formations are called “microbialites.” They are microbial mats that “petrify” themselves, meaning their biological activity transforms over time into solid layers of minerals.

Carbon Sponges

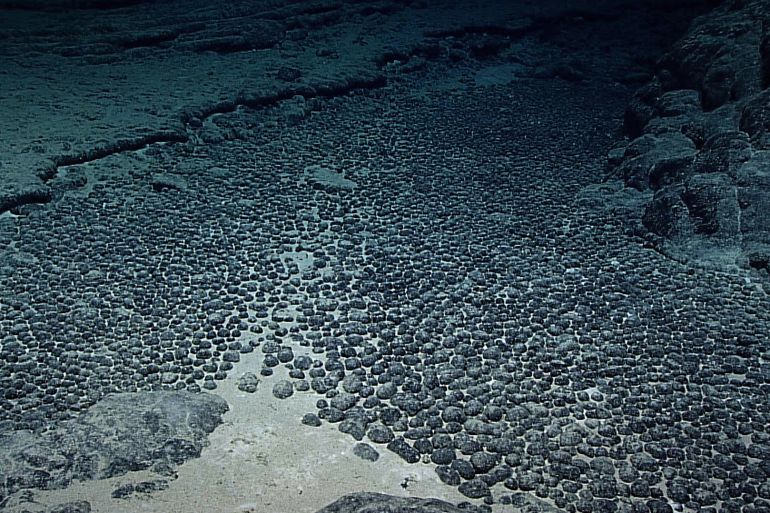

A new study, published in the journal Nature Communications, has shown that the microbialites in South Africa absorb carbon with high efficiency and trap it in the form of calcium carbonate, a stable, long-lasting mineral deposit.

In other words, part of the carbon dissolved in the water does not remain in a fast cycle that could return it to the atmosphere. Instead, it is locked in stone, thanks to these fossilizing bacteria.

This is important. We know that carbon dioxide is the primary gas responsible for the global warming crisis, so absorbing it would undoubtedly help address that problem.

The basic idea is similar to what coral reefs do, but performed by microbes. These microorganisms absorb carbon and deposit minerals, building up successive layers.

![Brazilwood, the national tree of Brazil, is endemic to the Atlantic Forest, which faces threats from deforestation and climate change [File: Bruna Prado/AP Photo]](https://libyawire.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/ss-3-1763971960.jpg)

Day and Night

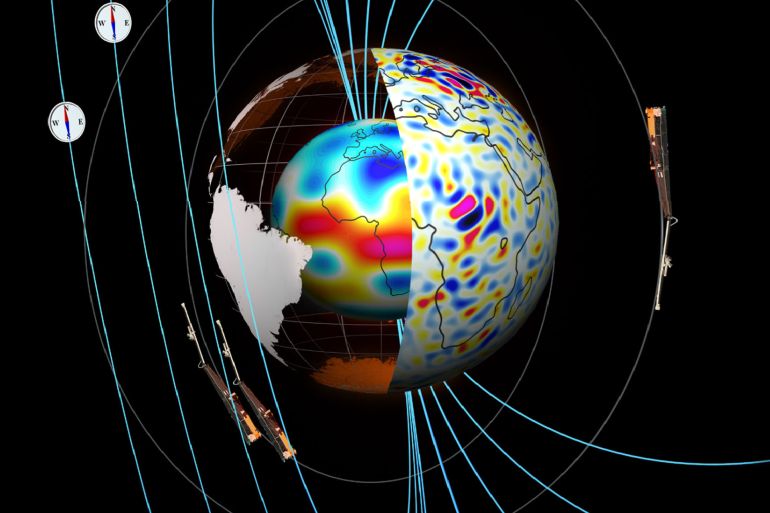

The new aspect here is that the research team linked the rates of carbon absorption and sedimentation to the genetic and functional capabilities of the microbial community. They didn’t just measure the amount of absorption; they tried to understand how it happens and who performs it within this complex community.

Even more surprisingly, absorption does not rely solely on photosynthesis (which stops at night). The results indicate that photosynthesis is also supported by mechanisms that do not depend on light, meaning this “carbon sequestration factory” may operate day and night.

Based on daily rate estimates from the study, these microbialites could absorb the equivalent of 9 to 16 kilograms of carbon dioxide per square meter annually. This is a striking figure when you consider it’s a small, naturally occurring system operating under harsh conditions.

Researchers compare this by saying an area the size of a tennis court covered by these formations could equal the annual carbon dioxide absorption of roughly 3 acres of forest.

Scientific Value

Note that what happens here is not biological storage, where carbon is stored in biomass that may decompose and return to nature. Instead, it is mineral fixation, involving the conversion of “carbon” into “carbonate” within layers that grow over time.

This type of sequestration is more stable. It is one of the reasons why microbialites are part of Earth’s long story with carbon, and the story of life itself.

Does this mean these ancient formations represent a magic solution to the climate problem? It’s not that simple. The study reveals strong natural potential, but it does not claim we can “offset” global emissions simply by relying on these formations. Area, distribution, and environmental sensitivity are critical factors.

The more immediate practical value today is to understand the mechanisms of natural sequestration more precisely and to consider these sites as systems worthy of protection because they perform a real environmental service, in addition to their scientific value as one of the oldest constructive forms of life on Earth.

In a future stage, scientists could develop the concept further, perhaps by innovating “biomineralization” technologies that mimic the