When evaluating a dance performance, one of the most important criteria is the harmony and synchronization between the dancers. If one of them loses the rhythm of the performance and their movements become discordant, it can lead to the collapse of the entire show.

Similarly, this is what happens in physics, chemistry, and materials science. The behavior of matter does not depend on a single, isolated electron, but on the harmonious movement of electrons with each other. This can lead to various phenomena such as the cohesion of atoms to form molecules, the electrical conductivity or insulation of materials, or the transfer of energy within a substance.

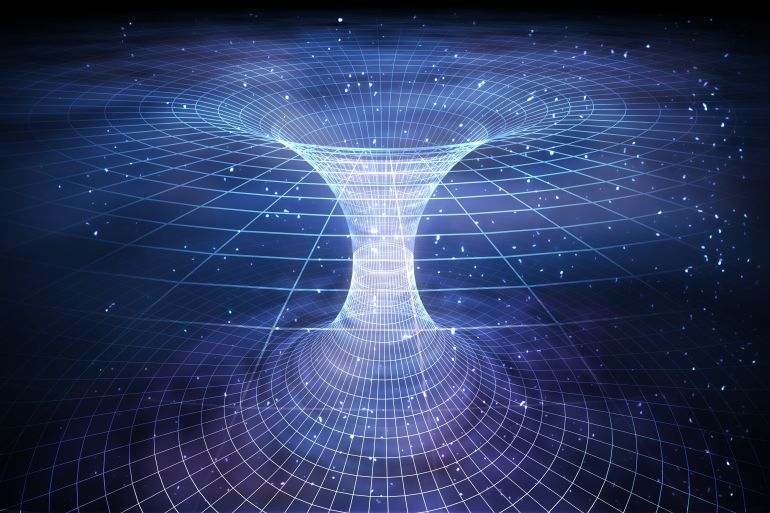

This harmonious interaction in quantum physics is known as “quantum coherence.” In technologies like quantum computing, information is stored in these “correlations” between electrons. When this harmony is lost, the information is lost—a phenomenon called “decoherence,” which is one of the biggest challenges facing quantum computers.

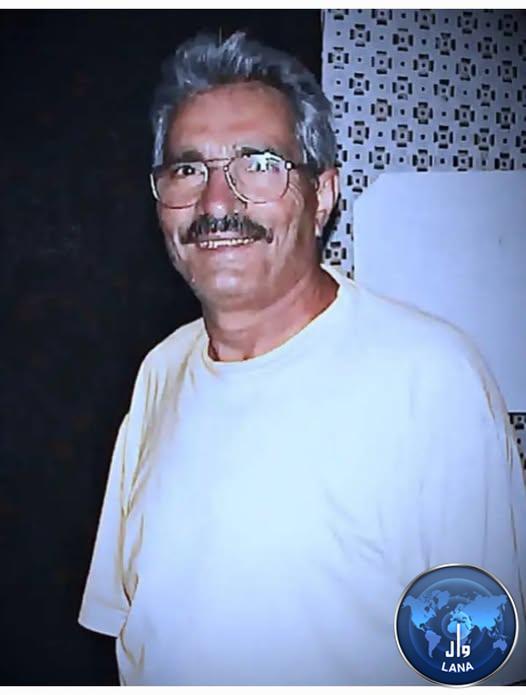

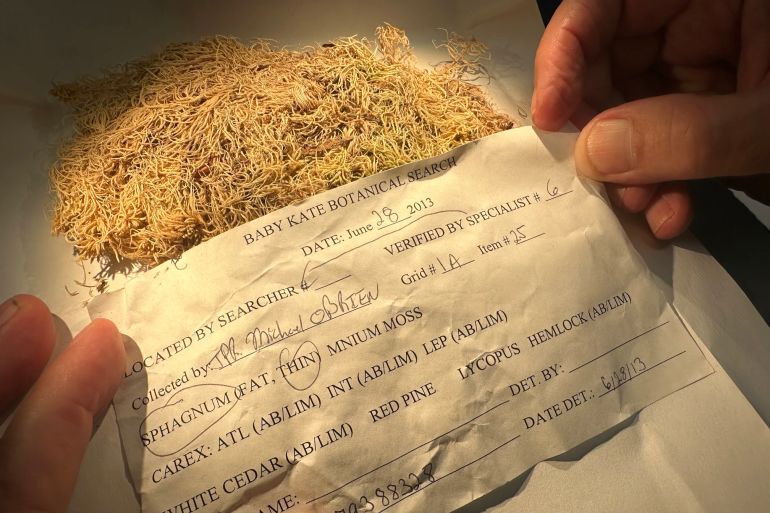

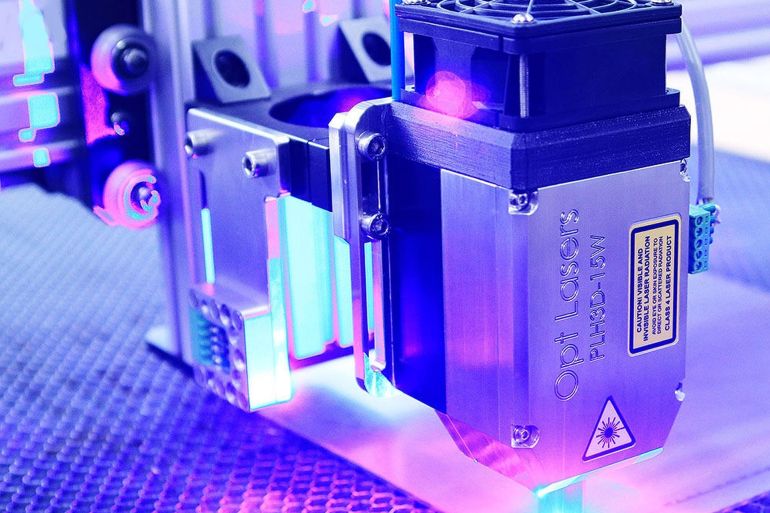

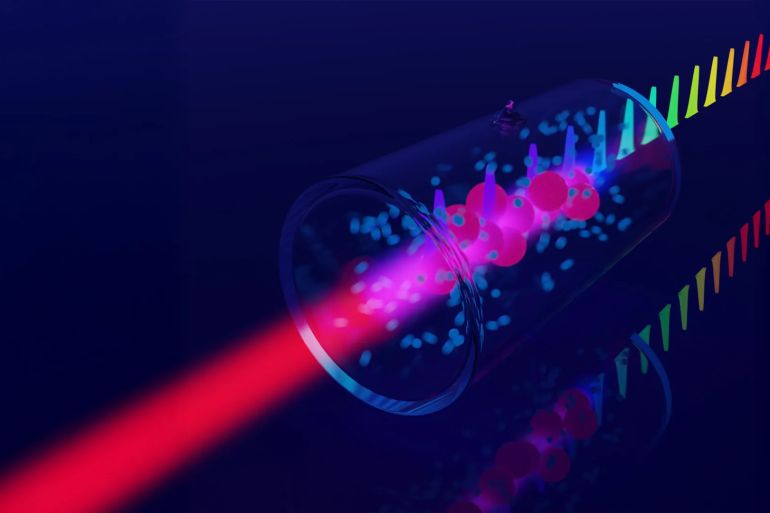

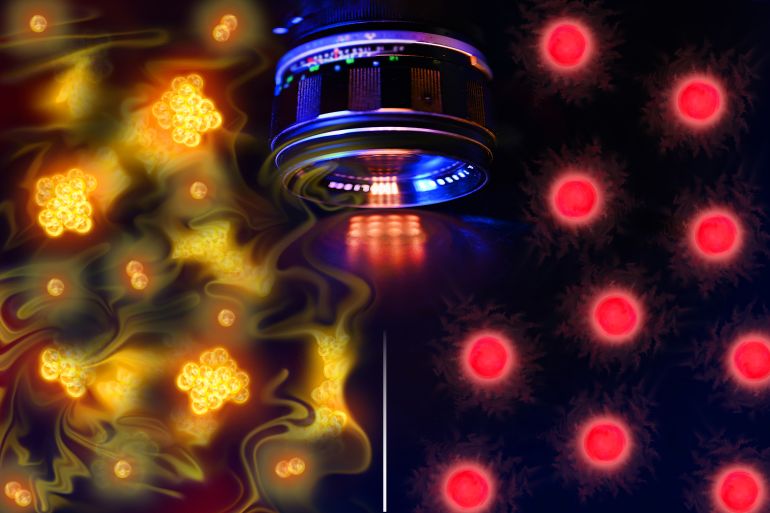

Due to the importance of this harmonious interaction, scientists have sought to observe these subtle relationships between electrons. However, the problem they faced was that most previous tools only allowed for observing the motion of a single electron. A scientific team has now overcome this problem using X-ray pulses provided by a Swiss free-electron laser facility.

This helped the scientists carry out an experiment long considered nearly impossible. They managed to see how electrons interact with each other within an atom or molecule—an achievement announced in the journal Nature and described as seeing the “dance of the electrons” together for the first time.

How was the “Dance of the Electrons” seen?

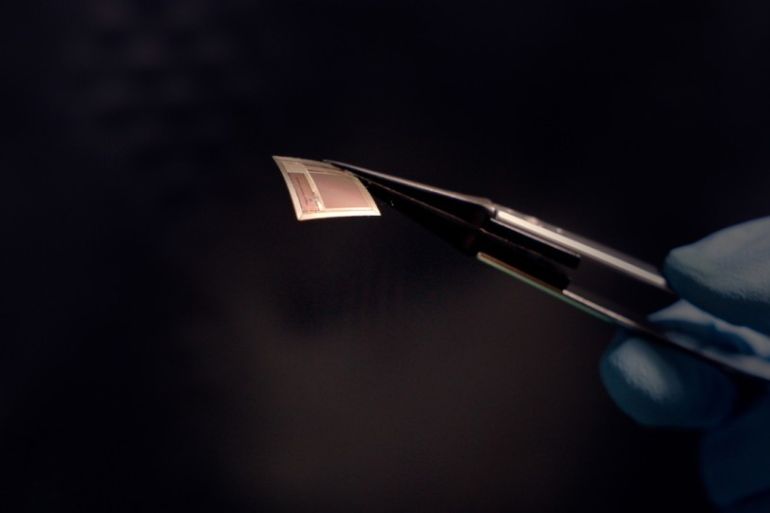

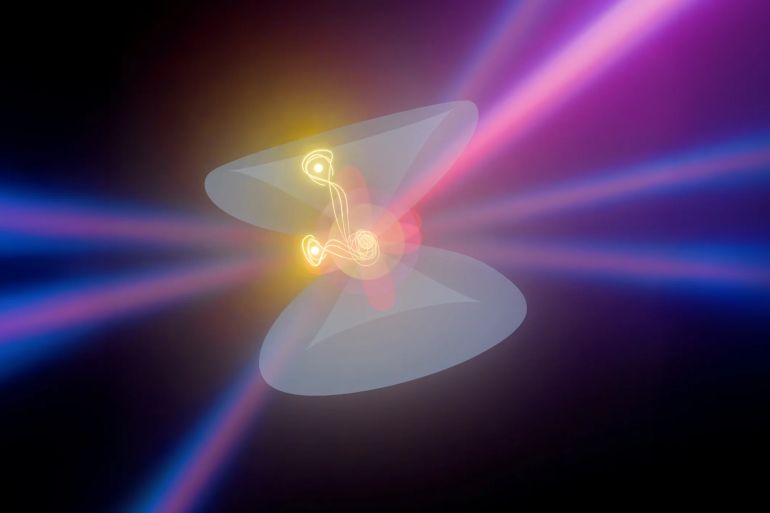

To achieve this feat, the scientists relied on ultra-intense, extremely short X-ray pulses provided by the Swiss facility. They sent three very precise X-ray pulses into the material. These pulses were so short that they could keep pace with the motion of the electrons themselves. Each pulse had a precisely calculated timing and direction—a task akin to trying to shoot three arrows from a distance of one kilometer to hit a target with extreme accuracy on the nanometer scale.

When these pulses are sent, they do not directly image the electrons. Instead, they perturb them slightly and force them to interact, so they no longer behave as separate particles but begin to respond collectively. As a result of this interaction, the radiation does not exit as it entered; a completely new fourth pulse is formed. This pulse is not created by the device but by the electrons themselves during their interaction.

This fourth pulse acts as a fingerprint of the relationships between electrons. Its shape, direction, and timing carry precise information about how the electrons interact with each other. In other words, we are now seeing what happens “behind the scenes” in the quantum world.

To illustrate what the scientists did, one can compare it to a composer striking three notes on a piano. The result the composer obtained was a new melody that reveals how the strings vibrate together, not just the sound of each string individually. Similarly, the scientists sent three pulses, and the fourth pulse revealed the collective motion of the electrons, not the motion of a single electron.

The ability to focus on the interactions between electrons allows for the possibility of providing entirely new insights. For example, in the field of quantum computing, it could enable the production of more stable computers less prone to information loss—one of the biggest challenges in this field. Potential applications also extend to designing new materials with improved properties for conducting or insulating energy, enhancing the efficiency of solar cells and batteries, as well as gaining a more precise understanding of the behavior of complex biological molecules.