Imagine a window that performs two seemingly contradictory functions: it lets in light and maintains clear visibility, while simultaneously acting as an insulating wall that slows heat transfer in both summer and winter.

This is the idea a team from the University of Colorado Boulder is trying to approach with a new material they have nicknamed “Mochi,” short for a highly transparent optical thermal insulator. This insulator is designed to be added to the interior of windows in the form of panels or thin sheets.

In the world of thermal insulation, walls can handle thick layers of insulation without issue, but windows are required to remain transparent. This is where the dilemma begins, as many materials that insulate well scatter light, making them appear “cloudy.”

For this reason, windows are a weak point in a building’s envelope, through which energy easily escapes. Buildings consume roughly 40% of the energy generated globally, and a significant portion of this consumption is wasted as heat that escapes to the outside in the cold or infiltrates indoors during extreme heat.

Transparent Silicon Gel

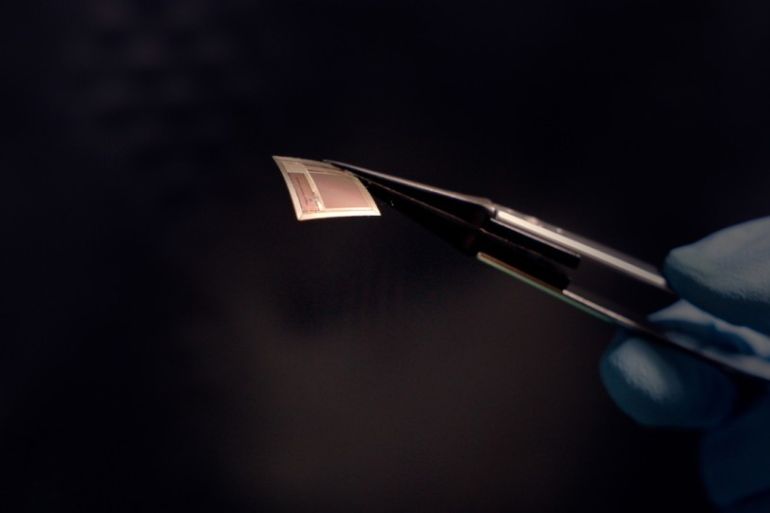

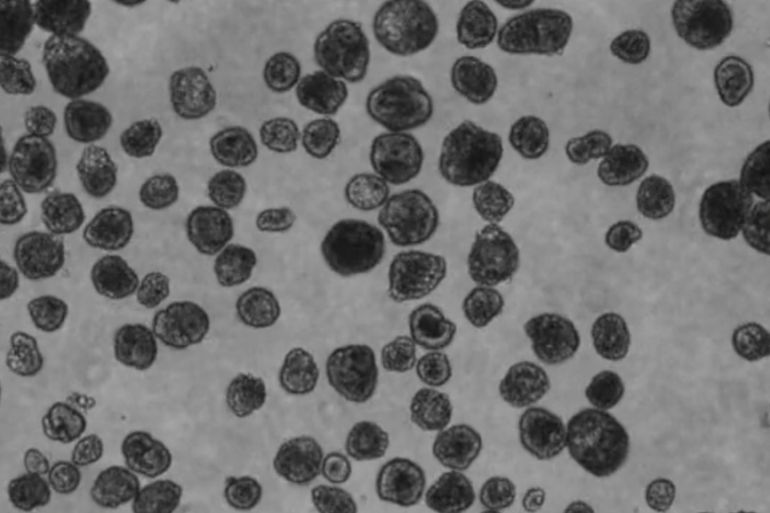

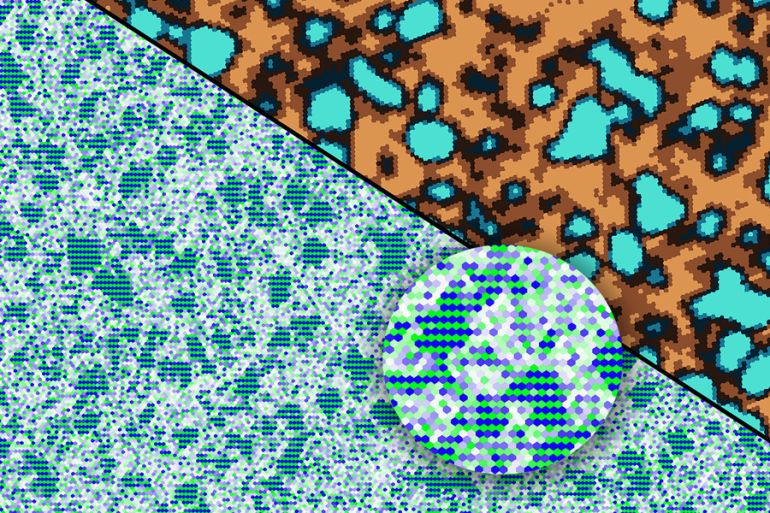

According to the team, the new material resolves this contradiction. It is a silicon-based gel, but its secret lies not in the silicon itself, but in what’s inside it: a network of extremely fine air channels and pores, much thinner than a human hair. Air constitutes more than 90% of the material’s volume.

This is the core idea. Instead of air voids being randomly distributed as in many porous insulating materials, the “Mochi” insulator aims to have them meticulously organized to reduce light scattering, keeping the insulator nearly transparent.

According to the study published in the prestigious journal Science, a 5-millimeter-thick sheet of this insulator was sufficient to allow a person to safely hold a flame directly against it without heat transferring quickly to the hand, while the material remained almost transparent.

This happens because heat transfer resembles a chain of collisions, where faster-moving molecules collide with each other, transferring energy. However, when these molecules are trapped inside extremely tiny pores, they can no longer collide freely with each other, weakening heat transfer.

The Future of the Industry

In the study, the researchers compare the new insulator to a well-known class of insulators called aerogels, sometimes described as “frozen smoke” because their porous structure scatters light, making them appear hazy. The difference here is that Mochi’s pores are not visually chaotic, thus preserving visual clarity. It reflects only about 0.2% of incident light, meaning most visible light passes through it, reducing the problem of window fogging.

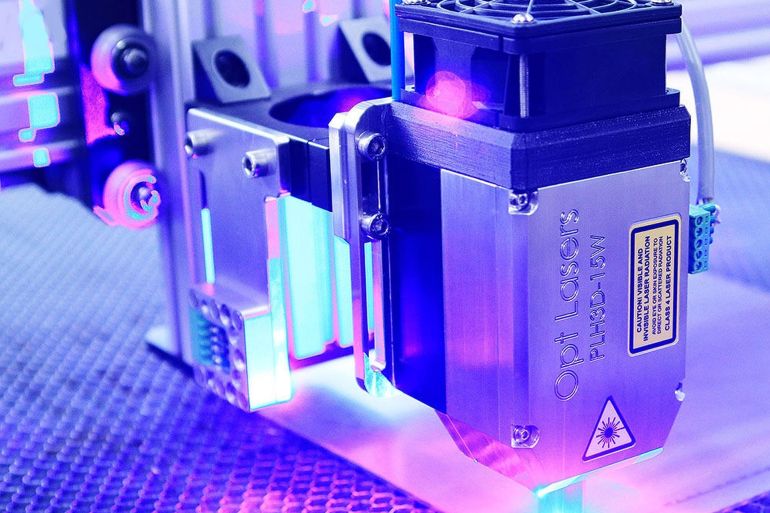

Creating this structure is not magic, but smart materials chemistry. The researchers mix molecules of “surfactants” within a solution, which naturally assemble into fine threads, a process they liken to what happens when oil separates from water.

Subsequently, silicon molecules adhere to the surface of those threads. The surfactant assemblies are then removed and replaced with air, leaving behind a silicon framework surrounding ultra-precise air channels.

So far, the new insulator is not yet commercially available, as its production remains laboratory-based and time-consuming. However, the researchers believe the manufacturing process can be simplified later and point out that the material’s components themselves are not expensive.