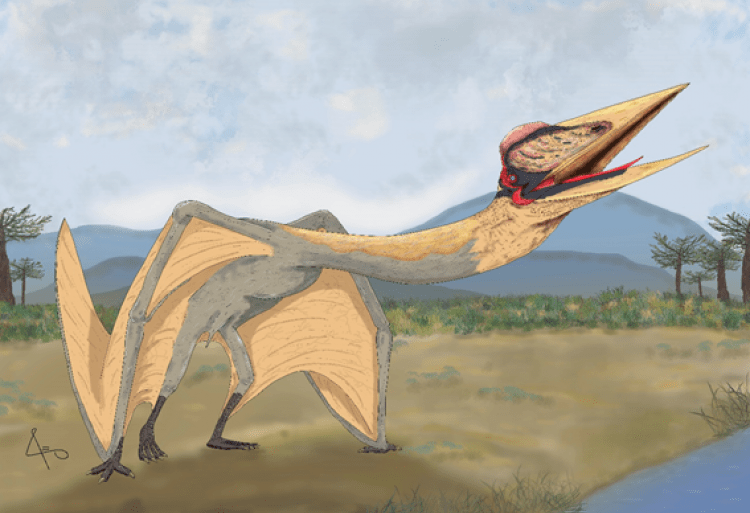

New research has revealed how pterosaurs—flying reptiles that lived before flying dinosaurs and today’s birds—possessed the necessary brain structure for powered flight.

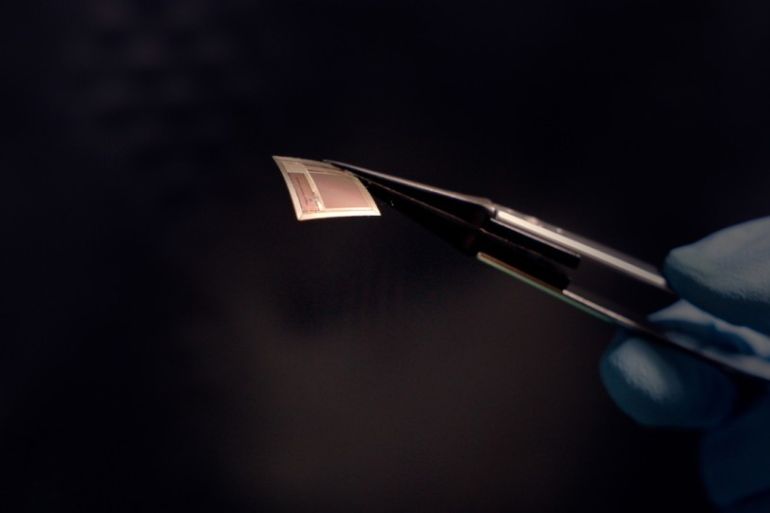

Using rare fossils and high-resolution 3D imaging techniques, a study recently published in the journal “Current Biology” traced step-by-step how the brain changed shape to allow these creatures to fly.

This “breakthrough” came with the discovery of a close ancient relative of pterosaurs, named “Exalerpeton,” from 233-million-year-old rocks in Brazil.

This discovery provided the first window into an early stage before the emergence of true pterosaurs, enabling the team to make comparisons with the brains of pterosaurs themselves.

Fossil Record

Scientists possess a rich fossil record explaining how the bird brain adapted for flight, while the evolutionary path of pterosaurs remained unclear.

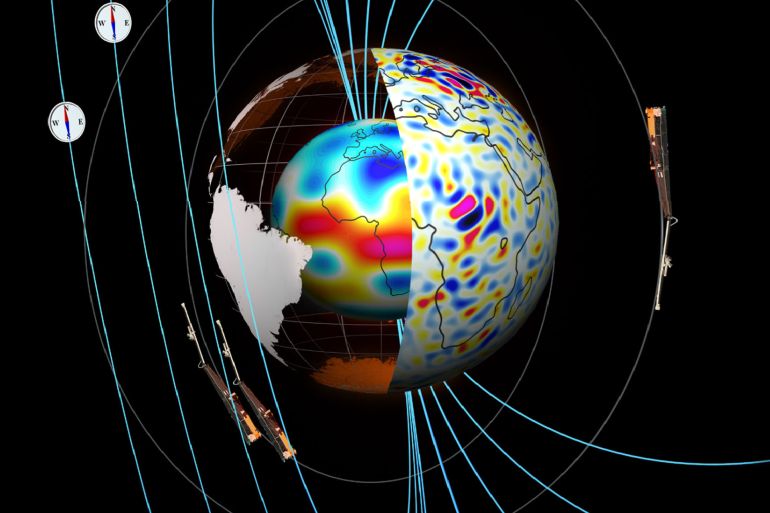

To investigate, the team studied more than thirty species of ancient and modern reptiles, including pterosaurs, their relatives like Exalerpeton, early dinosaurs, as well as modern crocodiles and birds.

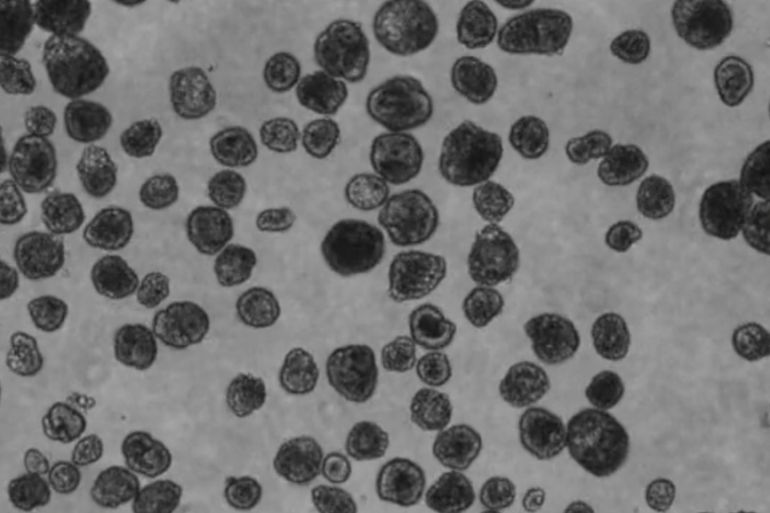

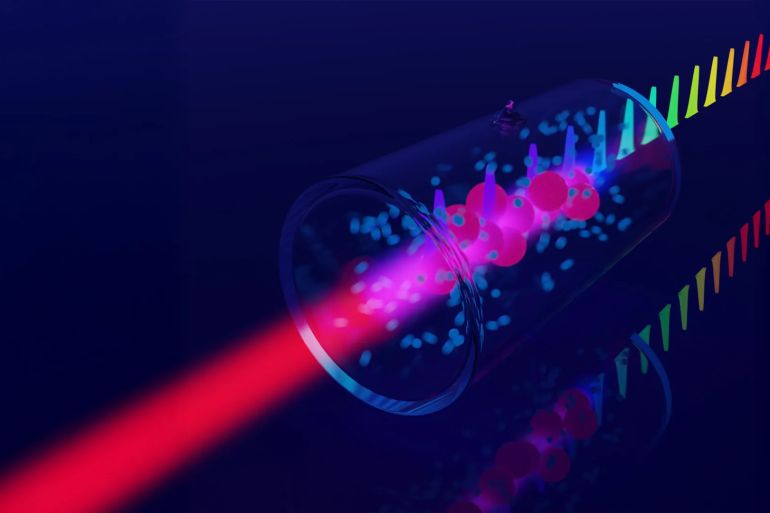

The researchers used computed microtomography, an advanced type of X-ray that produces precise 3D sections of the skull. From these images, they reconstructed the shape of the internal cranial cavity, which roughly reflects the shape and size of the brain.

The team then numerically analyzed the size and dimensions of different parts of this cavity to map the changes that accompanied the emergence of winged flight.

“It is known that flight is an extremely complex effort, requiring instantaneous coordination between vision, balance, and wing movement. Previous studies had indicated similarities between pterosaur brains and bird relatives like Archaeopteryx, particularly in the enlargement of parts of the cerebellum and regions responsible for vision (the optic lobes).”

“The new aspect of this study is that Exalerpeton—an ancient relative likely living in trees—showed some signs of improved visual capability, such as enlarged optic lobes. However, it simultaneously lacked key elements that later appeared in pterosaurs and seem to have been necessary for effective powered flight.”

A notable difference is a small part of the cerebellum called the “flocculus,” a region that helps the brain stabilize vision during movement by integrating information from the eyes, inner ear, and wings.

In pterosaurs, this part was greatly enlarged, likely helping them keep their eyes fixed on a target while flying swiftly through the air. In Exalerpeton, the flocculus remained modest in size, closer to other reptiles and early birds, suggesting its enlargement appeared later with the completion of true flight capabilities.

The Secret of Pterosaur Brains

It was also shown that pterosaur brains themselves were not large. “Despite some similarities with birds, pterosaur brains were much smaller. This means you don’t need a big brain to fly.”

The study concludes that the large brain size in birds was likely associated with increased intelligence and complex behaviors, not with flight alone.

Interestingly, the general shape of pterosaur brains resembles the brains of small, bird-like dinosaurs (like troodontids and dromaeosaurs), even though the latter were not capable of strong flight, if they flew at all.

The core idea proposed by the team is that there were two nearly independent paths to flight in vertebrates: the bird path and the pterosaur path. Both paths achieved the ability to fly, but each followed a different “neural solution.”