From intensifying storms to harsh cold waves, from drought to heatwaves, everyone is noticing that extreme weather phenomena are currently more widespread than ever before.

For example, people in the Arab world have known about heatwaves since ancient times and called them ‘Al-Waghrat,’ but these waves are now longer, more severe, and recur at higher rates than in the past, to the point where the entire summer feels like one major heatwave. So, what is the reason for all this?

Climate extremes are not a new type of weather as much as they are a logical consequence of heating up an entire system that was tuned to precise balances for thousands of years.

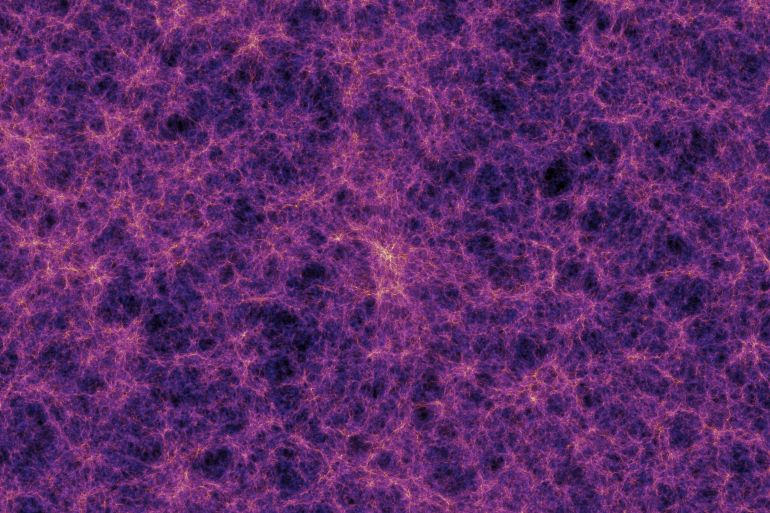

When the atmosphere and oceans warm due to the accumulation of greenhouse gases, weather averages shift. More importantly, the “tails of the distribution” move with them.

What are the Tails of the Distribution?

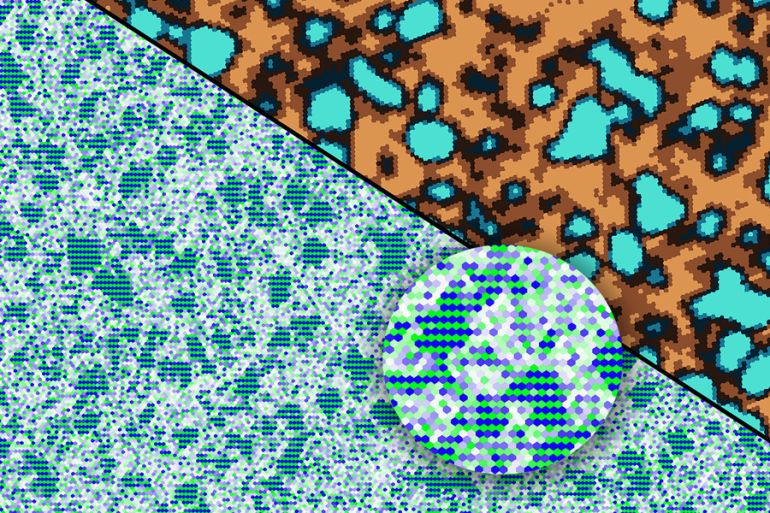

To understand the idea, imagine temperatures throughout the year as a bell curve, the one we studied in school. In the middle are the normal days that occur frequently. On the two ends are the very rare days: a very hot tail (record-breaking heatwaves) and a very cold tail (harsh cold waves).

These tails are what scientists mean by “tails of the distribution”; they represent the extreme cases that occur infrequently compared to the rest of the days. When the climate warms and the overall average temperature rises, not only does the middle move, but the entire curve shifts upward. Days of extreme heat move from being rare to being more frequent, and record-breaking temperatures become easier to achieve.

Then comes a factor that amplifies the effect: soil dryness. On hot summer days, moist soil cools the air through evaporation. But with increasing heatwaves and repeated drought periods, the soil dries out earlier. This disables the natural cooling brakes, and more radiation goes directly into heating the air, causing the heatwave to intensify and last longer.

This is described as one of the “compound events,” meaning the danger does not come from a single phenomenon alone, but from the coincidence of two or more phenomena where each worsens the other. A heatwave dries out soil and plants quickly, and with dry soil, the evaporation that naturally cools the air decreases. As a result, the sun’s energy goes into directly heating the air instead of evaporating water.

The result is a feedback loop: heat increases drought, and drought increases heat. This prolongs the wave and intensifies its impacts on agriculture, wildfires, and water resources.

What About Humidity?

The second major reason, which also explains more severe floods and heavier storms, is that warm air holds more water vapor.

A famous thermodynamic rule called the Clausius-Clapeyron relation states that the air’s capacity to hold moisture increases by about 7% for every one-degree Celsius rise in temperature.

This means extra “water fuel” for any cloud or storm. When conditions are right, rain falls more heavily and in a shorter time, increasing the likelihood of flash floods.

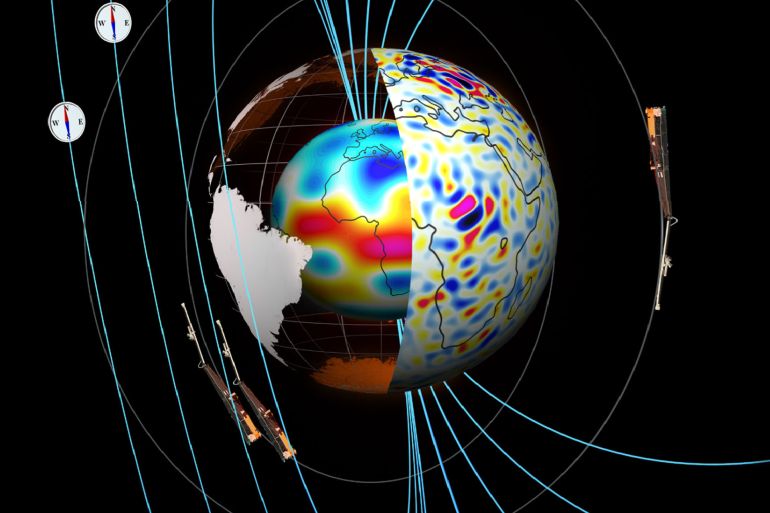

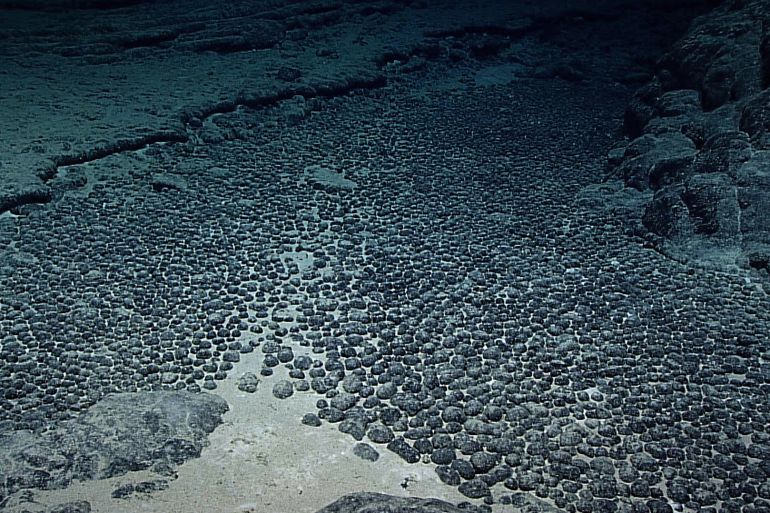

Since the oceans are the largest thermal reservoir, their warming changes the dynamics of the entire atmosphere. Rising sea surface temperatures and ocean heat content increase evaporation, raise the moisture available for storms, and fuel phenomena like marine heatwaves that can affect marine food chains.

For tropical cyclones, they resemble an engine that draws its energy from sea surface heat. Higher sea surface temperatures mean greater potential energy, and warmer air means heavier rain within the cyclone