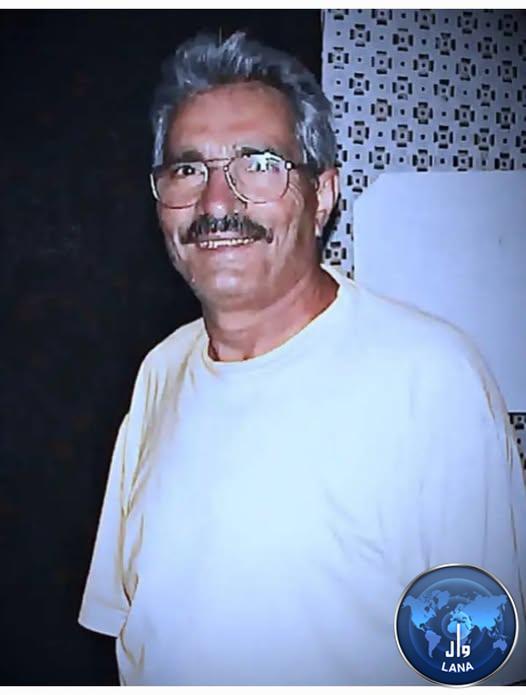

On October 17, 1902, investigators arrived at the scene of a horrific crime in Paris, where a man named Joseph Reibel had been killed at his workplace with no eyewitnesses.

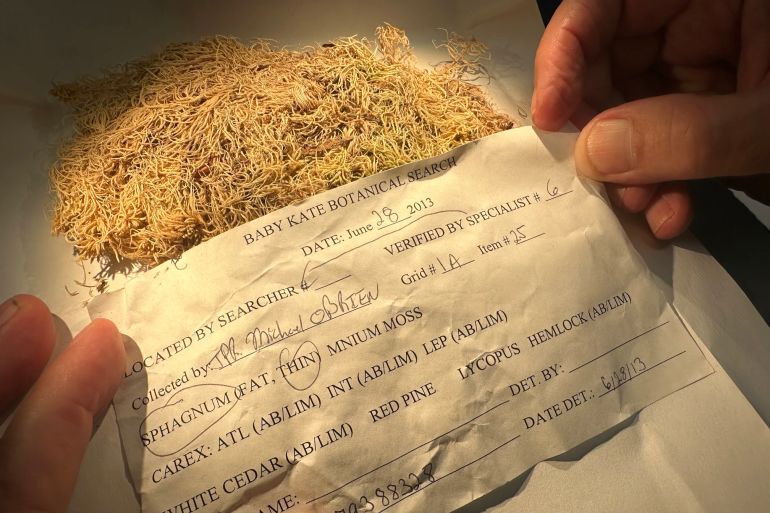

The officers had little to go on until they discovered a broken piece of glass, bearing several blood-stained fingerprints.

An investigator manually searched through fingerprint records at the police station and eventually found a match. “Henri Scheffer” had been arrested on theft charges the previous year and later confessed to the murder.

This was the first time in Europe that investigators had solved a crime using fingerprints alone. More than a century later, fingerprints remain a crucial factor in criminal cases and one of the most common types of evidence in criminal courts.

However, in recent years, doubts have been raised about the reliability of this type of evidence, with criminal justice advocates expressing concerns about the potential for wrongful convictions based on fingerprints. To what extent can they be relied upon absolutely for delivering verdicts?

The Fingerprint as Incriminating Evidence

Humans are born with patterns of raised ridges and sunken grooves, not only on their fingers but also along their hands and feet. These features help provide a stronger grip, especially on wet surfaces, and increase tactile sensitivity.

Many experts believe that each person has a unique fingerprint, and it is unlikely that any two fingerprints, past or present, are completely identical. They are different even between identical twins, influenced by genetic and environmental factors.

People have likely known the nature of fingerprints for centuries. Leaders of ancient civilizations like the Babylonians and Chinese imprinted fingerprints on clay tablets and wax seals, using them as signatures or personal marks. However, fingerprints did not become an effective tool for fighting crime, nor did scientists begin studying their various characteristics and classifying them, until the late 19th century.

The British scientist Sir Francis Galton was the first to place the study of fingerprints on a scientific foundation, paving the way for their use in criminal cases. He was not the first to suggest using them for identification; in 1880, Dr. Henry Faulds published a letter in the journal “Nature” proposing the use of fingerprints as a means of identifying criminals.

Galton studied thousands of fingerprints and proved that no two are exactly alike; even identical twins have different fine ridge patterns and swirling minutiae. He created a detailed system for classifying fingerprints, allowing for their efficient organization and comparison.

Galton’s pioneering work forever changed forensic science. Most importantly, his broad advocacy for the use of fingerprints helped convince a skeptical public that they could be reliably used for personal identification, providing a permanent, stable, and unique record that still helps solve mysteries to this day.

Suddenly, law enforcement agencies around the world had a new, reliable method for identifying criminals and solving cases that previously seemed impossible. Suspects could no longer simply disappear into crowds, hoping to escape justice without leaving a trace.

By the early 20th century, prosecutors began using fingerprints in court, forever changing how investigators handled and analyzed crime scenes.

Fingerprints Today

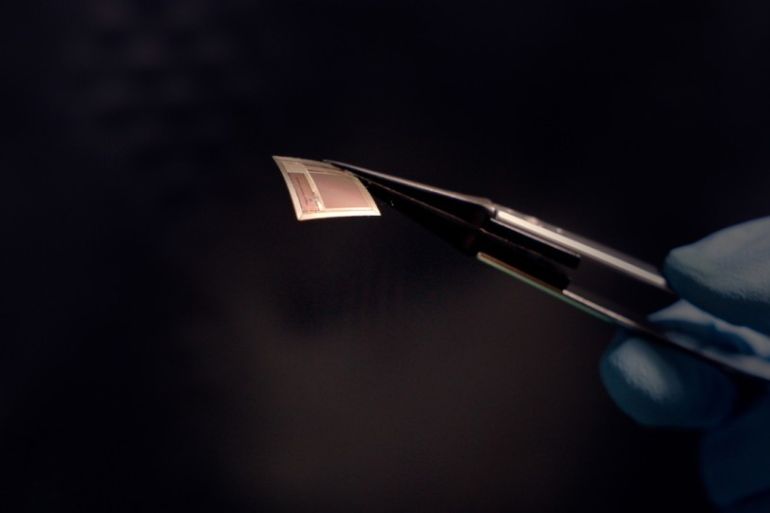

Fast-forwarding to today, fingerprint technology has come a long way from just magnifying glasses and ink pads.

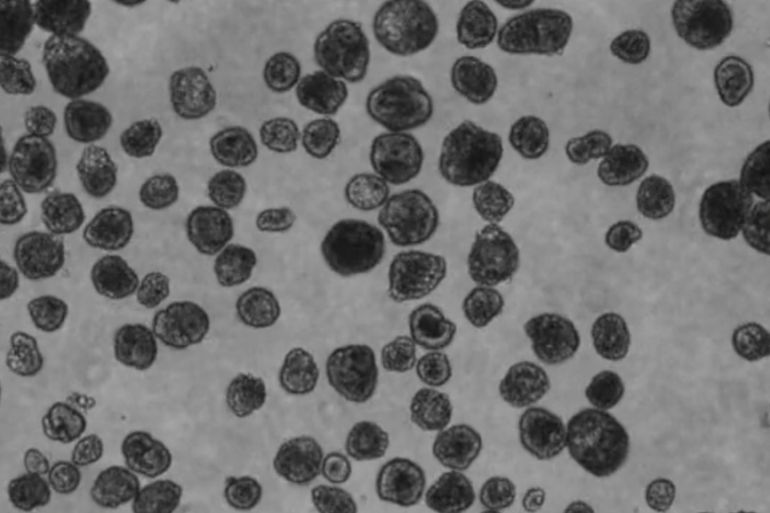

Investigators today often begin by searching for visible prints, which include patent prints formed when blood, dirt, ink, or paint