- The Crime of Dopamine: How Do Psychological and Social Dynamics Exploit Our Failure to Manage Boredom?

Last November, media outlets circulated shocking news about the reopening of a criminal investigation in Italy regarding what was called “murder tourism” during the siege of Sarajevo in the 1990s. Foreigners paid huge sums for the opportunity to shoot civilians from the hills surrounding the besieged city, for entertainment and to experience the “thrill of real sniping,” in one of the most horrific war crimes of modern Europe.

The details of the investigation reveal that these crimes were not driven by national hatred, religious fanaticism, or ideological motives, although the presence of some of these factors is hard to deny. Their basis was simpler and more dangerous: a pathological attempt to escape boredom and stimulate the dopamine hormone at any cost.

This terrifying scene is not much different from what is happening today in Gaza or Darfur, with the difference that we are dealing with killers who had no cause, who did not fight for a homeland or a creed, or even for money, but rather ordinary people who paid their money to fill their inner void by firing bullets at innocent bodies. They grew tired of virtual killing in video games and sought a “real-life version” of the game.

Here emerges the most dangerous image of the crime of dopamine, when the search for euphoria turns into a killing machine, and boredom becomes an instigator of crime. A frightening question imposes itself: what if boredom is one of the hidden drivers of the most horrific forms of human violence?

And if some kill others to escape boredom, do we not practice another kind of killing? We kill ourselves, our time, and our lives by wasting them in front of smart screens, searching for meaningless entertainment that grants us short-lived, worthless highs.

From teenagers’ addiction to smart screens, violent games, and pornographic sites, to activists and influencers participating in hate speech and incitement, to some preachers engaging in excommunication and defamation, and finally to politicians’ involvement in genocide crimes or ordinary individuals joining dangerous terrorist gangs—these phenomena seem disparate, but they intersect in one hidden thread: the failure to answer one question: how do I get rid of boredom?

This hypothesis may seem strange if we do not notice that many of our individual and collective decisions start from a small moment of boredom, in which we search for a quick stimulus, a temporary high, or a sense of meaning, even if it is false.

History has witnessed horrific stories, both mythical and real, about how a mistake in answering the question of how to get rid of boredom turned into brutal crimes, from the stories of Scheherazade and One Thousand and One Nights, to what is told about the nobleman in the European Middle Ages

Boredom: The Blessing That Turns into a Curse

This does not mean that the feeling of boredom is a sin or an evil in itself. Rather, it is a divine blessing placed in humans to be a driver for work, creativity, and meaningful change. But this blessing turns into a curse when we fail to answer an essential question: how do we get rid of boredom in a productive way?

In this context, it becomes important to distinguish between two types of boredom:

- The first is “boredom of inner emptiness,” which arises from the absence of purpose or self-discipline and leads its owner to quick distractions and digital addiction.

- The second is “boredom of realistic frustration,” resulting from the accumulation of disappointments and social and economic constraints, causing a person to lose motivation and seek excitement outside themselves.

The first type of boredom generates existential confusion that leads to amusement and addiction, while the second creates psychological pressure that may turn into anger, or even extremism and violence.

The failure to deal with this feeling in both states causes a person to drift towards quick painkillers instead of confronting the root of the problem. In both types, the search for quick stimuli and instant rewards to soothe the feeling of emptiness or frustration becomes the goal. These stimuli are often easy but destructive because they generate a false sense of satisfaction and kill patience and perseverance.

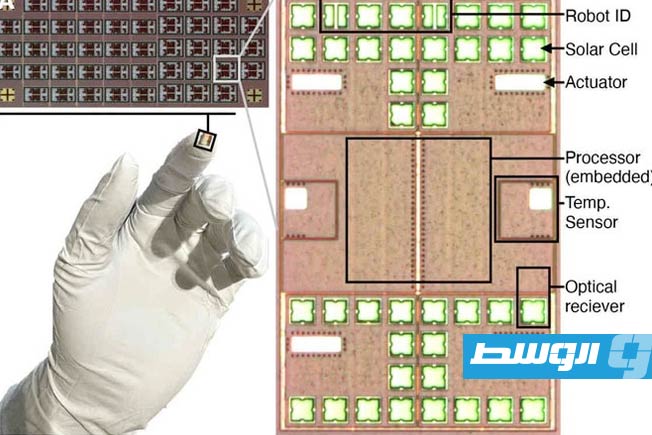

The human mind, in its quest to end the painful state of boredom, seeks an immediate reward from the “dopamine hormone.” From