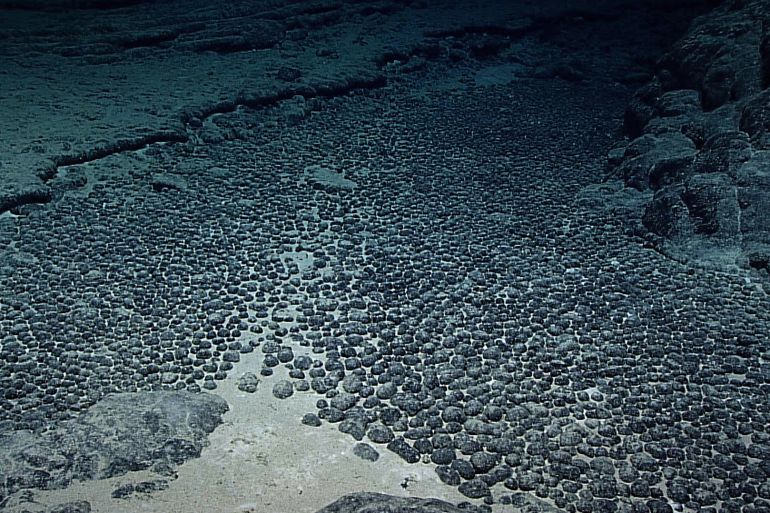

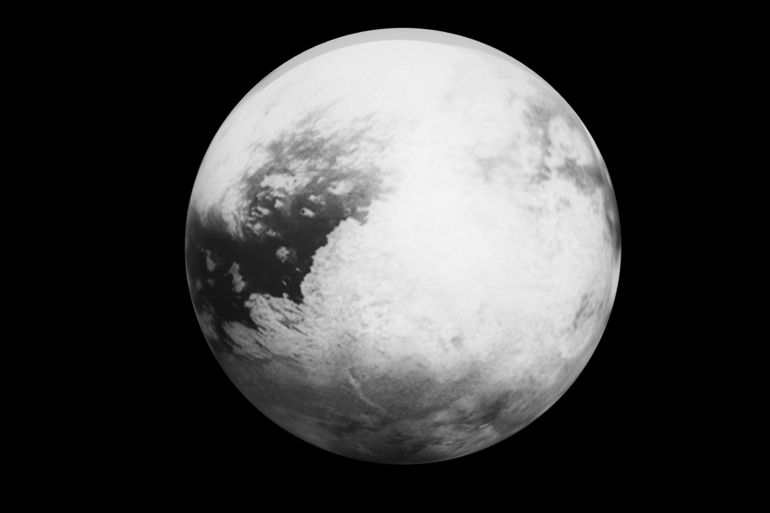

On January 19, 2026, the Chinese Shenzhou-20 return capsule landed safely in Inner Mongolia after spending 270 days in space, concluding a mission that was less ordinary and more a genuine test of China’s ability to handle the worst-case scenarios of modern spaceflight. So, how did the adventure unfold?

Hundreds of kilometers above the Earth’s surface, where absolute silence reigns and there is no room for error, China found itself facing one of the most difficult tests in the history of its manned space program.

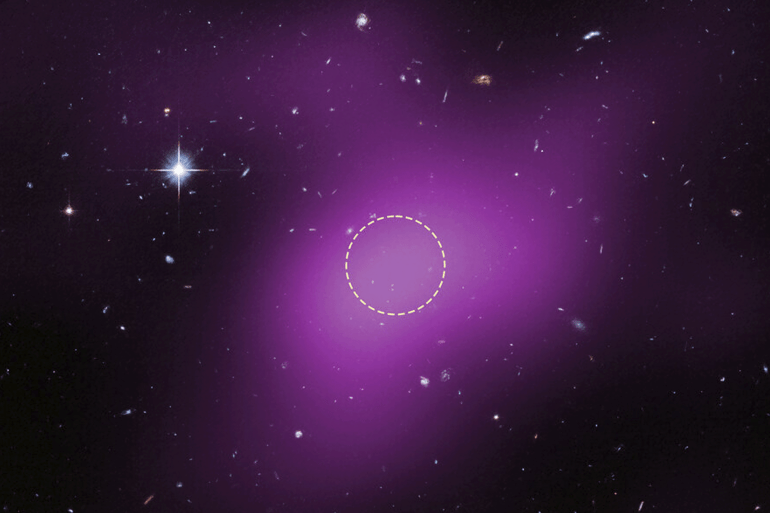

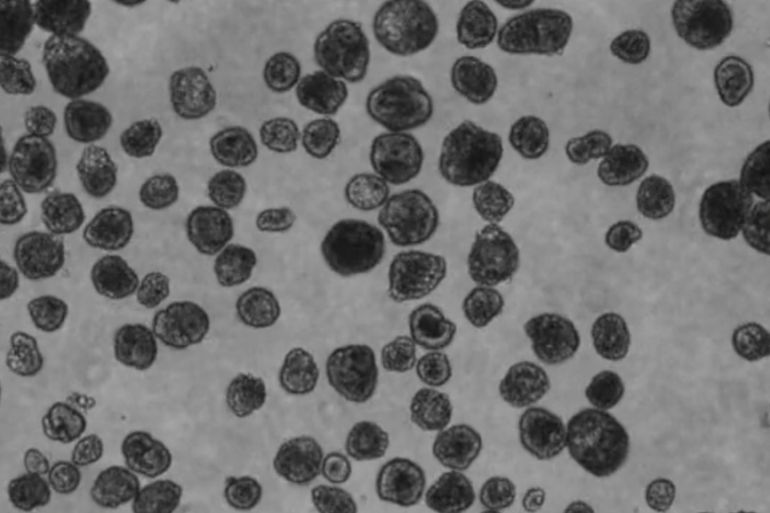

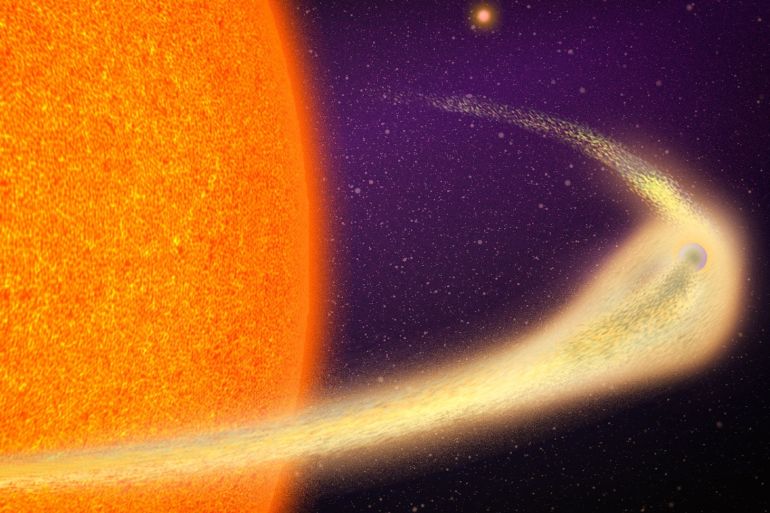

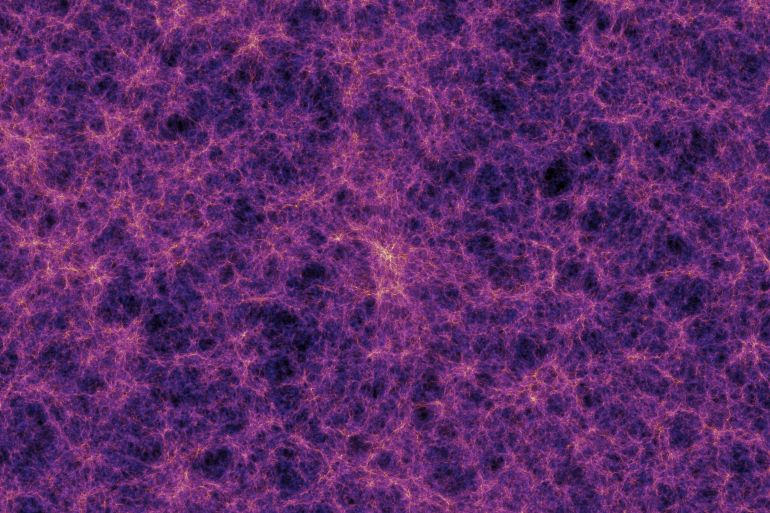

There was no sudden explosion or loud malfunction announcing danger, only fine cracks in the window of the Shenzhou-20 return capsule, later determined to have been caused by an unexpected collision with space debris orbiting in Low Earth Orbit.

In space, a small flaw can be enough to turn a successful scientific mission into a human tragedy. But in Chinese control centers, the question was not *whether* the spacecraft could be returned to Earth, but a more critical and sensitive one: how to first guarantee the safe return of the human crew, regardless of the technical or temporal cost of the decision?

A Decision That Settles Everything: Astronaut Lives Above Any Achievement

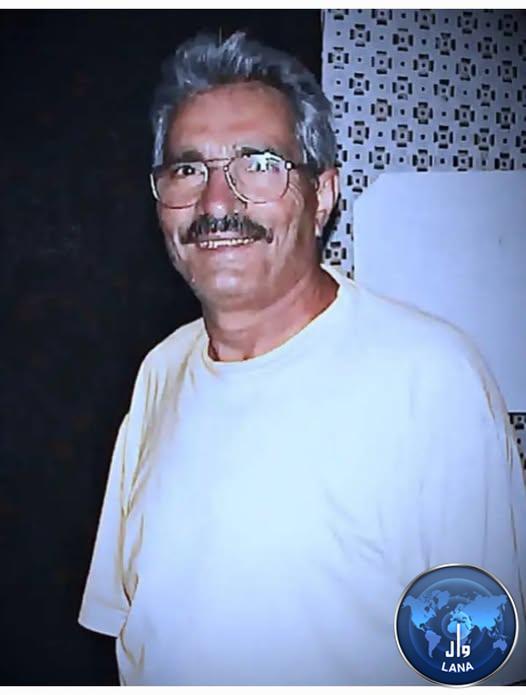

At that moment, three astronauts were aboard the Chinese Tiangong space station, having completed long months of scientific experiments and precise work in orbit. Upon confirming the presence of the cracks, Chinese space authorities made an irreversible decision: not to risk returning the astronauts in a capsule that might not withstand the harsh conditions of re-entry.

Instead, a quiet but highly complex emergency plan was executed. The astronauts were returned safely to Earth aboard the Shenzhou-21 spacecraft, while the Shenzhou-20 was left unmanned in orbit.

This was not a retreat from the challenge, but the beginning of a new, bolder chapter, where the crisis transformed into an unprecedented engineering test of China’s ability to manage risks in space without sacrificing a single human life.

Engineering Over Luck: Repairing a Spacecraft in Orbit

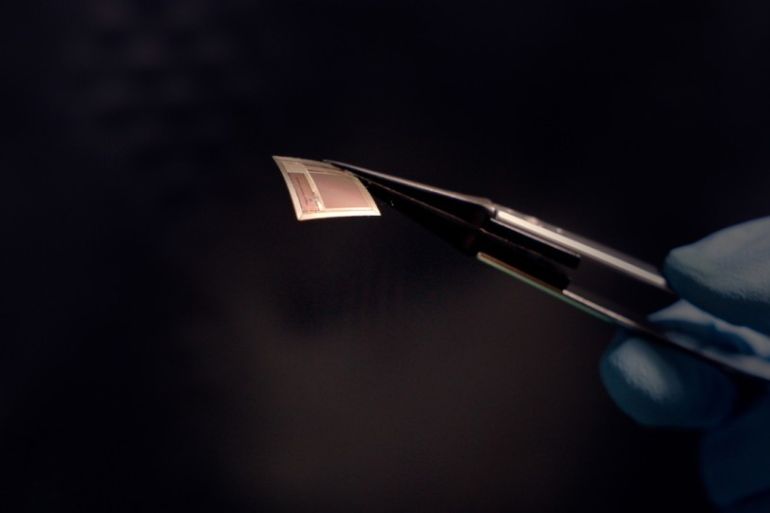

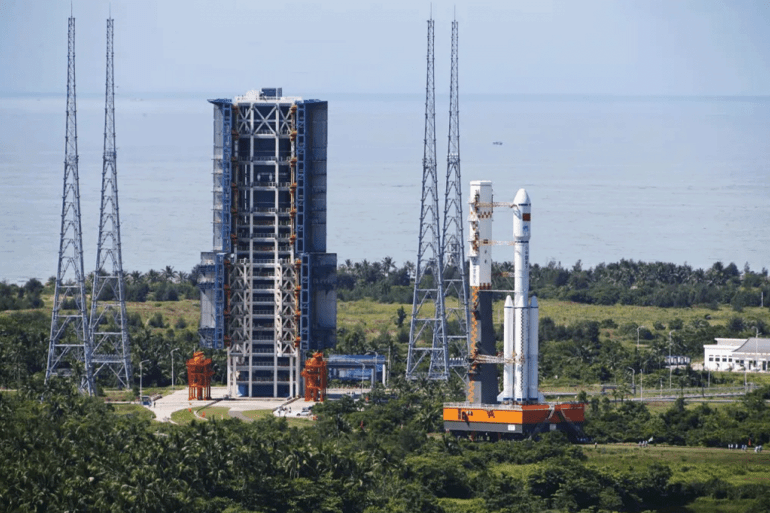

After securing the astronauts’ safety, the greater challenge began. The Shenzhou-22 spacecraft was launched on an emergency mission, carrying equipment specifically designed to enhance the protection of the damaged capsule and increase its ability to withstand the immense heat generated during atmospheric re-entry.

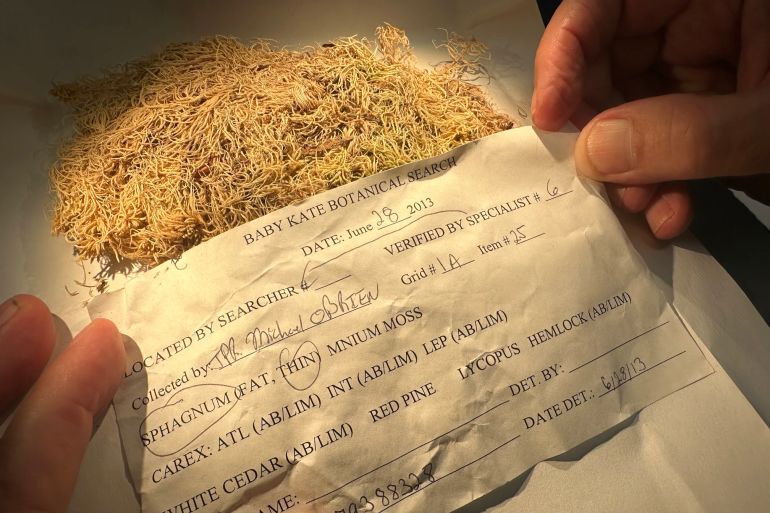

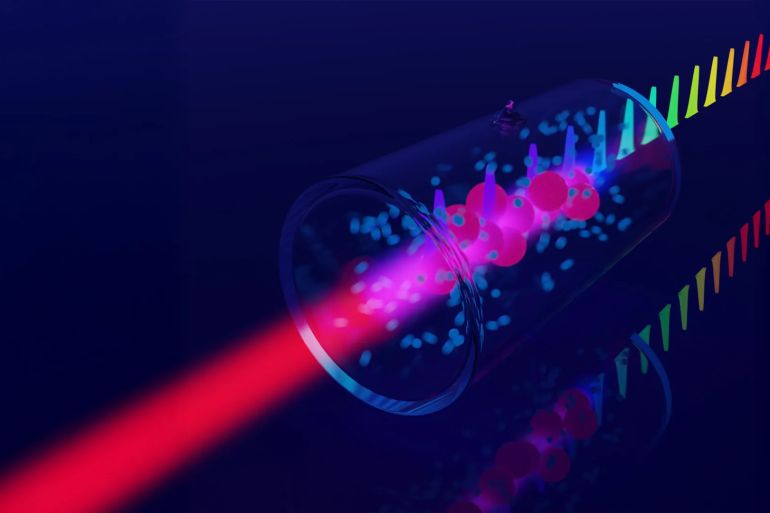

For the first time during the full operation of a Chinese space station, the damage was precisely diagnosed via space imaging. Thermal and structural modifications were carefully calculated and implemented, and the capsule’s balance was meticulously readjusted to compensate for the absence of the astronauts’ weight, replaced with scientific payloads to ensure the vehicle’s stability during descent.

All these operations were executed remotely from Earth, without direct human intervention in space—a scene reflecting an advanced level of coordination between human and machine, and between political decision-making and precise engineering.

The Silent Return: An Unmanned Vehicle and a Completed Mission

On January 19, 2026, after 270 days in orbit, Shenzhou-20 began its final journey. It carried no astronauts, but it bore a real test of a nation’s ability to fully control the fate of a damaged vehicle during one of the most dangerous phases of any space mission.

The capsule pierced the atmosphere, faced temperatures measured in thousands of degrees, and then landed safely in Inner Mongolia, confirming a simultaneous technical and human success.

This was not merely the return of a spacecraft, but a clear message that China’s achievements are measured not just by the number of flights, but by its ability to conclude them safely, even in the worst scenarios.