Scientists have recently explored the intricate details of a special kind of war waged beneath the bark of spruce trees, one fought not with tanks and bombers but with highly precise chemical interactions.

Spruce is a common name for evergreen trees, typically conical in shape, belonging to the pine family. They are usually characterized by short needles and hanging cones, are widely used for timber and paper, and live in cold and temperate forests across Europe, Asia, the Americas, and other regions.

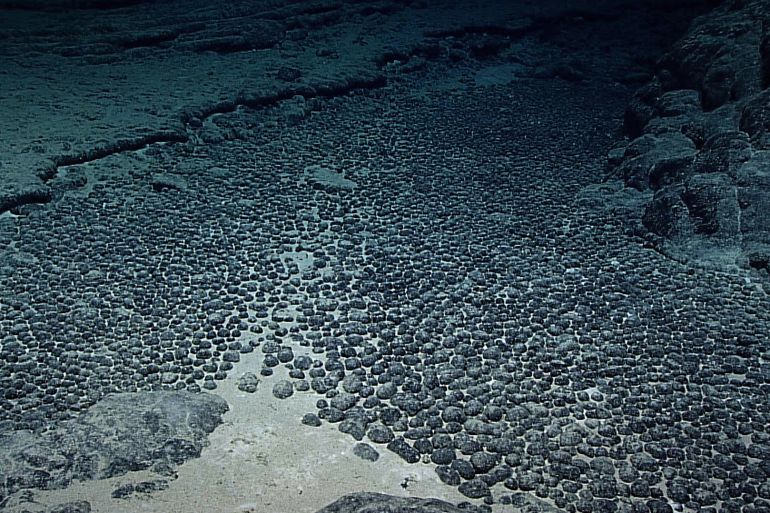

It is known to scientists that these trees defend themselves with a complex mixture of antifungal chemical compounds. On the other hand, the bark beetle, as its name suggests, tirelessly bores its tunnels into the spruce bark and not only tolerates these chemical toxins but coexists with them.

Chemical Secrets

But the new twist in the story, as revealed by a new study published in the journal PNAS, is that the beetle recycles the tree’s toxins to create an effective shield against fungi living in the same place.

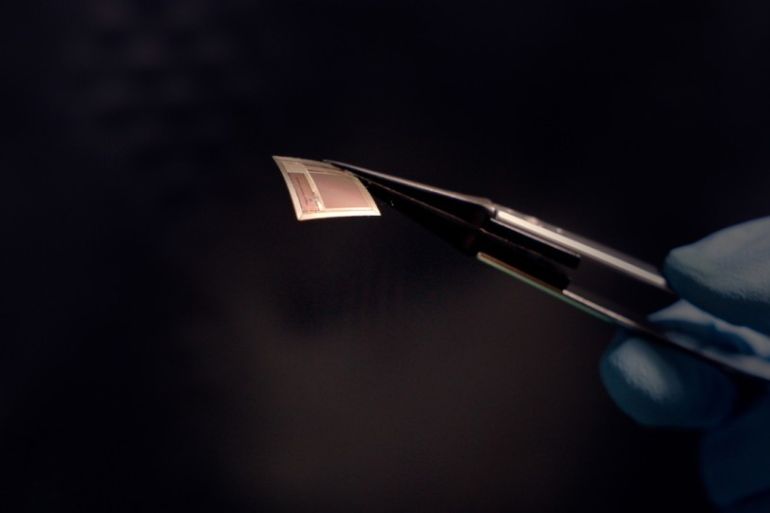

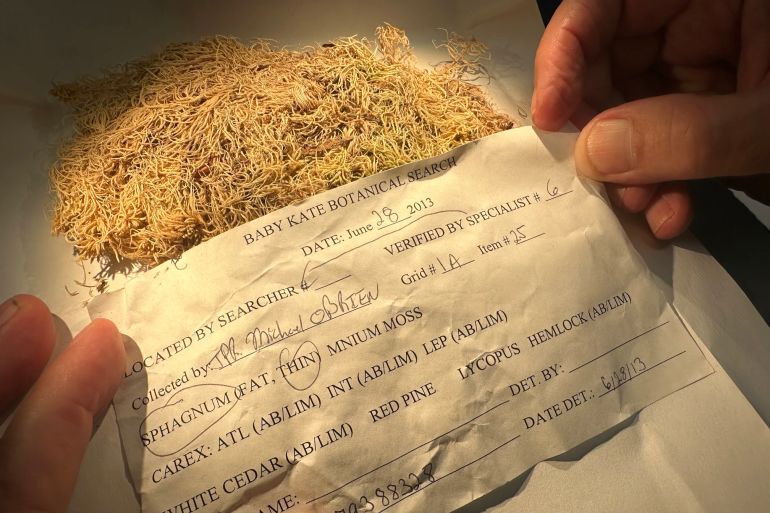

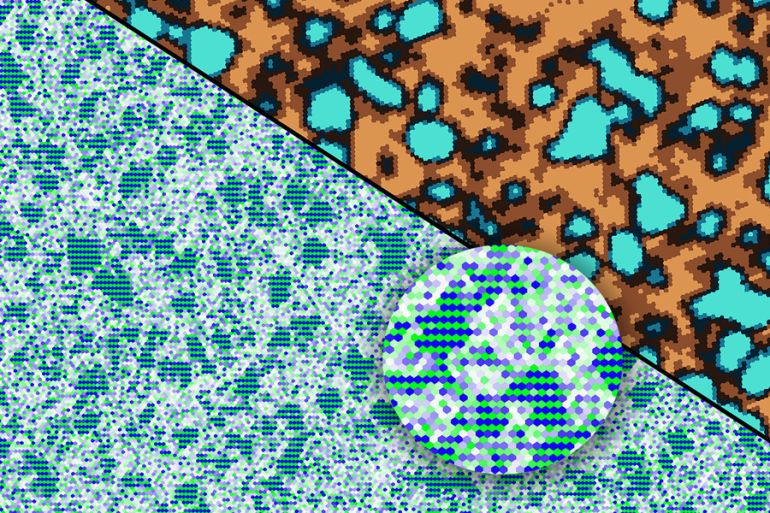

Chemistry has revealed the secrets of this process at a detailed level. Spruce bark is rich in phenolic glucosides, compounds that help the tree resist pathogens.

When the beetle consumes the bark tissue, it breaks the sugar bond in these compounds, producing other compounds called “sugar-free aglycones,” which are typically higher in antifungal activity. Thus, the tree’s defense, designed to protect it, becomes an additional protective layer on the insect’s own body.

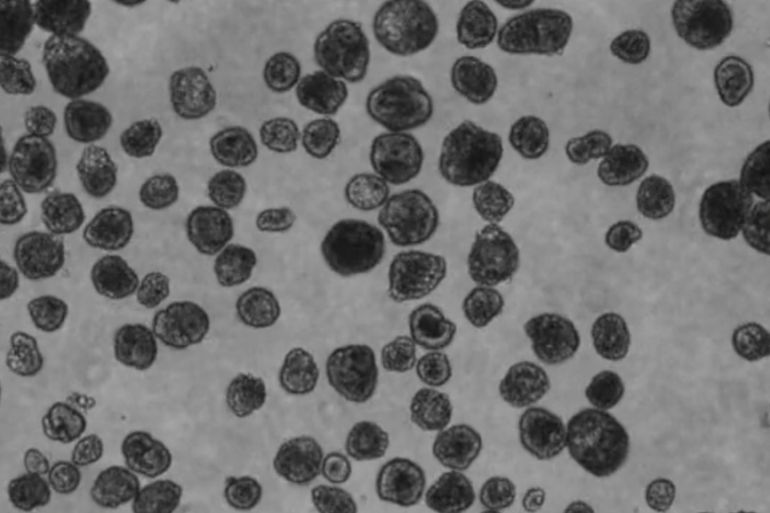

But the story doesn’t end there. Nature is variable, and there is a fungus known in the world of biological insect control called *Beauveria bassiana*. Scientists considered this fungus a promising option against many pests, but its effectiveness against bark beetles has been unsatisfactory.

A Borrowed Chemical Shield

The study suggests a possible reason: the beetle is protected by a chemical shield “borrowed” from the tree. However, some strains of the fungus appear to have adapted to this, developing a way to disarm this shield.

The mechanism discovered by the researchers is exquisite from a purely chemical perspective. It is a completely counteractive pathway targeting detoxification in two steps. The first involves re-adding a sugar to the aglycones, and the second involves adding a chemical group called “methyl,” transforming the toxic compounds into derivatives harmless to the fungus.

According to the study, these chemical processes proceed in one direction, stabilizing completely in this form and preventing the beetle’s enzymes from attempting to reactivate their toxicity.

This discovery might seem relevant only to the study of a highly interactive and complex biological world, but it has important applications. It changes how scientists think about biopesticides—methods of pest control that rely on living organisms or their natural products, such as bacteria and fungi, instead of traditional chemicals.