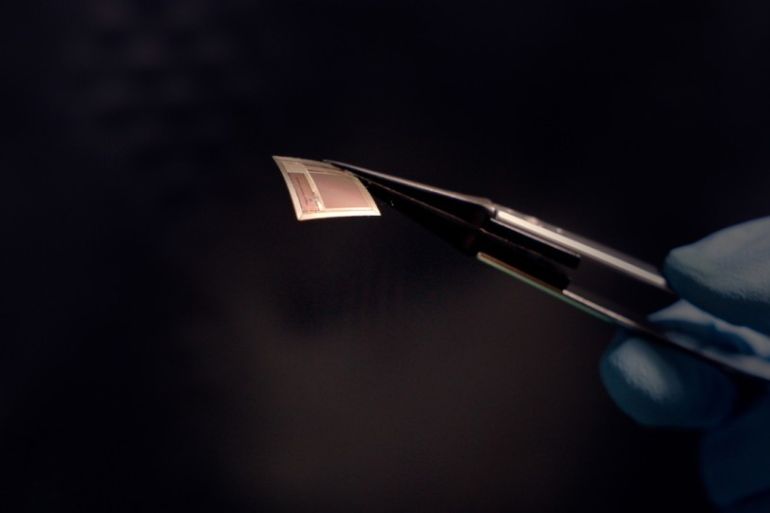

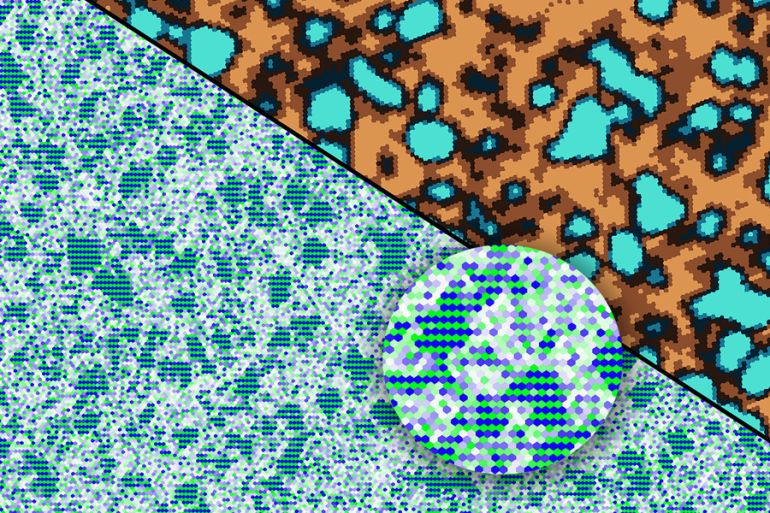

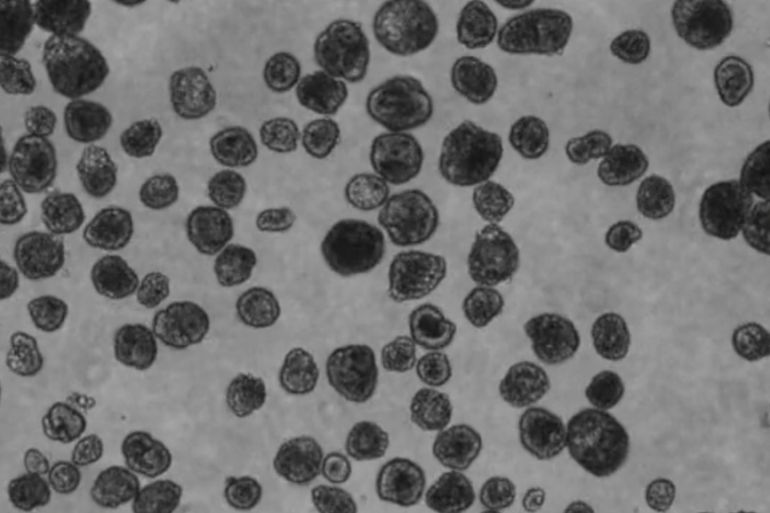

The cell wall is typically known as a thin membrane separating the inside from the outside. However, scientists have recently discovered that it represents a physical piece capable of converting motion into electricity.

This is the core of a new idea proposed by a research team, via a mathematical model showing that the vibrations of tiny cell membranes can generate electrical potential differences, as if the membrane is a very small power generator.

A potential difference is simply the “push” that makes electric charges move from one point to another, similar to how a difference in height pushes water to flow, and it is an indicator of electricity passing through.

A Very Small Electrical Generator

Inside the cell, proteins change shape as they perform their functions, and there are chemical reactions that release energy to keep the system chemically alive.

One of the most important of these processes is the breakdown of molecules called adenosine triphosphate, which represents the cell’s primary fuel. These molecules generate small forces that press on and stretch the membrane, causing it to bend and oscillate on the nanoscale.

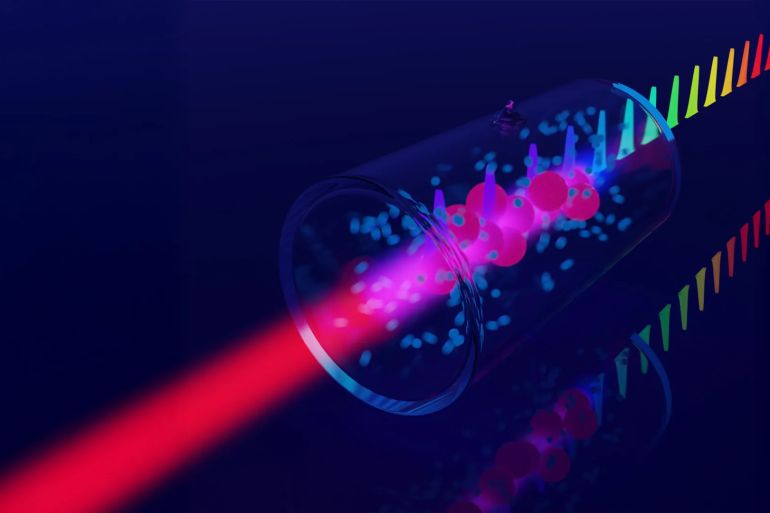

According to new research published in the journal PNAS Nexus, these small forces can generate electricity through a physical phenomenon called flexoelectricity, where the bending of the membrane generates electrical polarization, and thus a potential difference across the membrane, which we know as “electricity.”

Promising Results

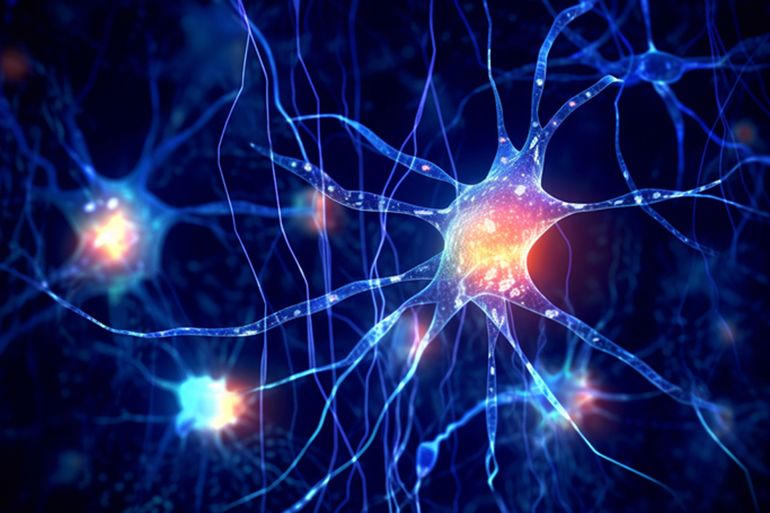

According to the results, the potential differences across the membrane can reach in some cases about 90 millivolts. Furthermore, these fluctuations can occur on a millisecond timescale, resembling the known potential differences in nerve cells.

In addition, the model developed by the researchers predicts that the electrical signals resulting from cell membrane oscillation may drive ions, which are charged atoms fundamental to cell balance and signaling, against the direction they naturally tend to go.

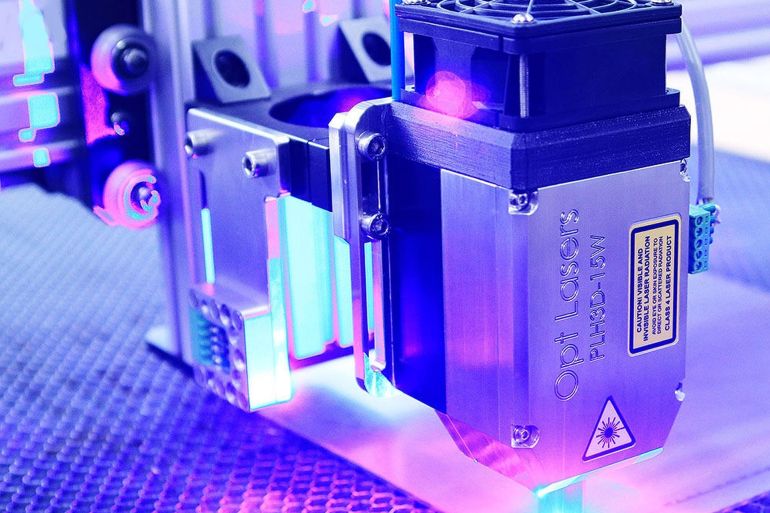

These results help scientists achieve a deeper understanding of the relationship between membrane mechanics and electrical signals, and what that might mean for processes such as sensation, cellular communication, and perhaps aspects of neural activity.

On the other hand, this could contribute to inspiring scientists to innovate bio-inspired materials and devices that combine flexibility and electricity, capable of converting subtle mechanical fluctuations into electrical signals—essentially smart materials in the physical sense.