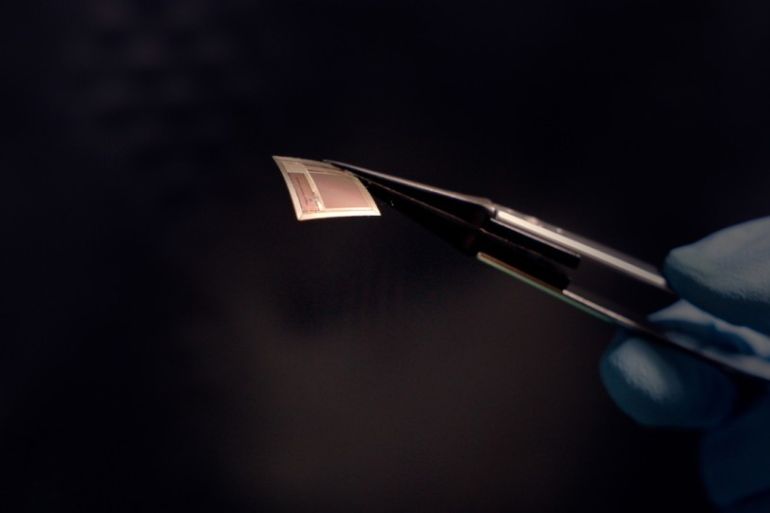

The movement of scientists between the United States and China is no longer just ordinary individual migration driven by personal motives. It has become part of a deeper landscape of competition between two global powers over funding, attracting scientists, publishing research papers, and within a political and security climate that is becoming increasingly sensitive in almost every corner of the world.

The result of this competition is that what was considered normal just two decades ago—studying in the United States and then settling long-term in its universities and laboratories—is beginning to crack in favor of returning to China or moving to other countries.

What Happened in Washington

At the beginning of 2025, the immigration issue in the United States entered a more stringent phase in both rhetoric and implementation. On January 20, 2025, a presidential order titled “Protecting the American People Against Invasion” was issued, changing the enforcement processes of immigration laws and explicitly linking the issue to national security and public safety considerations.

This type of order not only changes the letter of the law but also alters the mood and daily behavior of the executive branch, which quickly reflects on foreign researchers’ sense of stability and universities’ ability to attract talent without fear of sudden rule changes.

In June 2025, the stringency took a clearer form through two parallel tracks. The first was the expansion of security vetting for study and exchange visas. The State Department announced it would apply comprehensive vetting, including the online activity of all applicants for student and academic exchange visas. This means the review will no longer be confined to academic documents or funding as was customary, but will also extend to the digital footprint.

The second track appeared with reports of a temporary freeze on new interview appointments for student and exchange visas in late May 2025, in preparation for expanding social media screening. This indicates these restrictions are no longer theoretical but have a direct impact on functional acceptance.

Then came a notable development in June 2025 with the announcement of entry and visa issuance restrictions against nationals of certain countries, citing deficiencies in vetting procedures and information exchange. This measure took effect on June 9, 2025.

On September 19, 2025, a presidential proclamation was issued restricting the entry of H-1B visa holders arriving from outside the United States unless the application was accompanied by a payment of $100,000 and for a limited duration.

This visa allows a U.S. employer to employ a foreign national in a “specialty occupation” that typically requires a university degree or equivalent experience. This visa was a tool for attracting talent to the United States, and has now become a path fraught with financial and regulatory risks.

If we were to summarize the U.S. government’s position in 2025 in one sentence from the perspective of actual policies, it is simply prioritizing the logic of “deterrence” and strict “security screening” over the logic of attraction and openness.

Reasons for Returning

However, the matter is not limited to recent events; it has deeper roots. In a research analysis tracking the institutional affiliation of researchers through their scientific publications, it was observed that more than 19,000 U.S. scientists left for other countries, including China, between 2010 and 2021.

The report found that the proportion of those leaving and heading to China rose from 48% in 2010 to 67% in 202