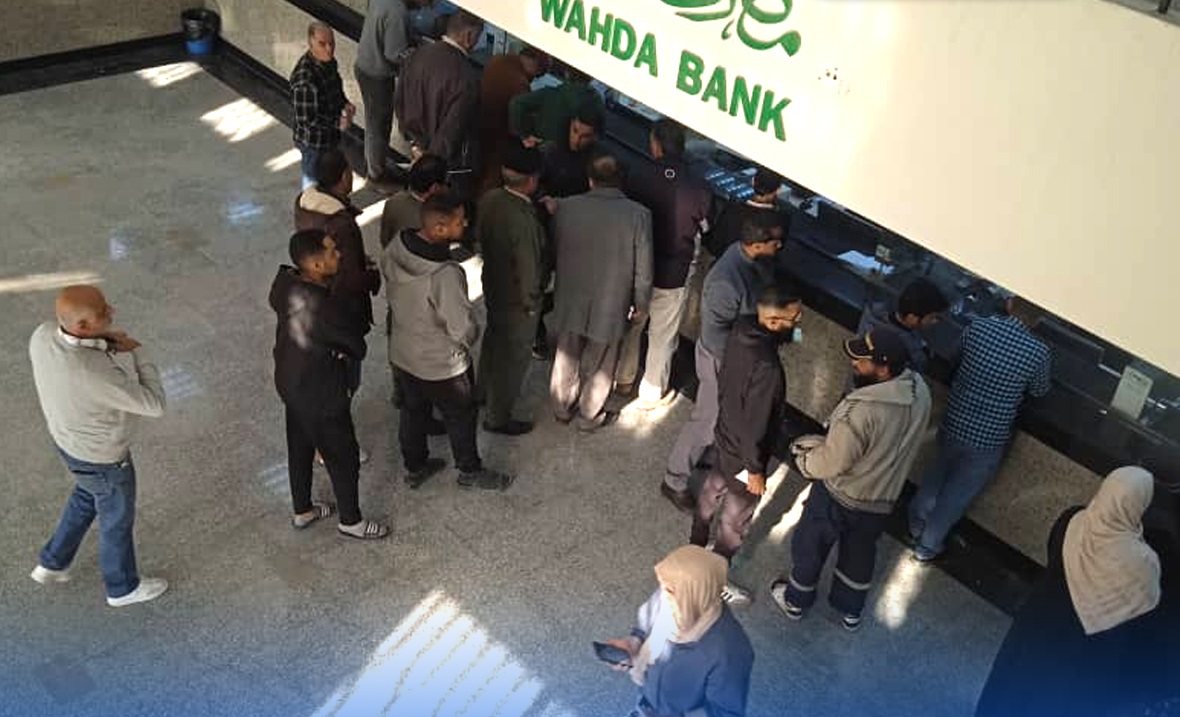

The Lebanese government approved, this Friday, a draft law on financial regulation and loss distribution, after more than six years of an unprecedented economic crisis that deprived Lebanese citizens of their deposits, despite opposition from political and banking forces to its provisions.

The government must refer the decree of the draft law to the politically divided parliament, as a preliminary step for its approval to become effective. This step is considered a key demand of the International Monetary Fund and experts deem it vital for economic recovery.

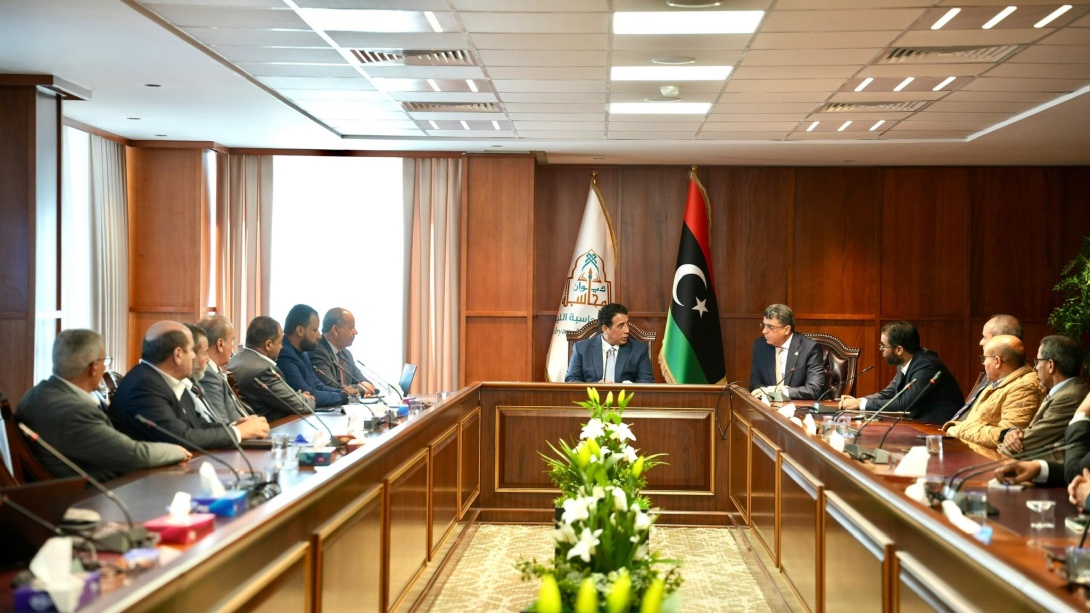

With the approval of 13 ministers and the opposition of nine others, the government approved the draft law on Friday, which stipulates the distribution of financial losses between the state, the central bank, commercial banks, and depositors.

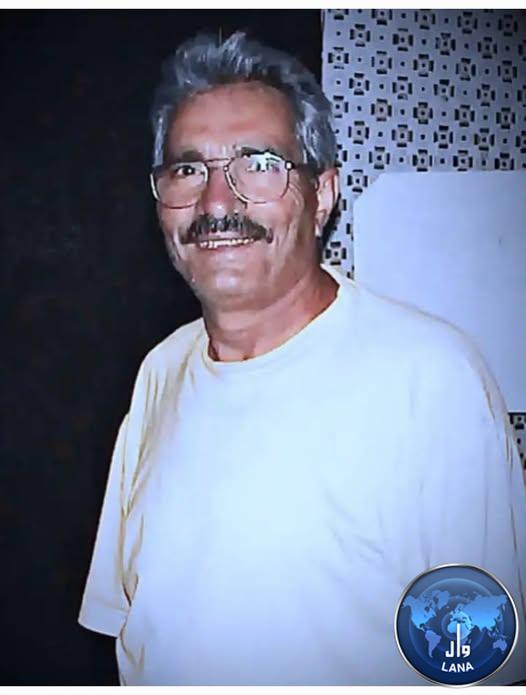

Following the session he chaired, the head of government said to journalists that the draft law is “not perfect, and may not meet everyone’s aspirations, but it is a realistic and fair step on the path to restoring rights, stopping the collapse the country is suffering from, and restoring health to the banking sector.”

The project, known as the financial gap law, represents a long-awaited essential step for restructuring Lebanon’s debts since the economic crisis that hit it in the fall of 2019. It is considered a cornerstone of financial and economic reforms. The international community, particularly the International Monetary Fund, demands its approval as a prerequisite for providing financial support to Lebanon.

Losses of 70 billion dollars

The government estimates the financial losses at around 70 billion dollars, an estimate that experts say has increased after six years during which the crisis remained unresolved.

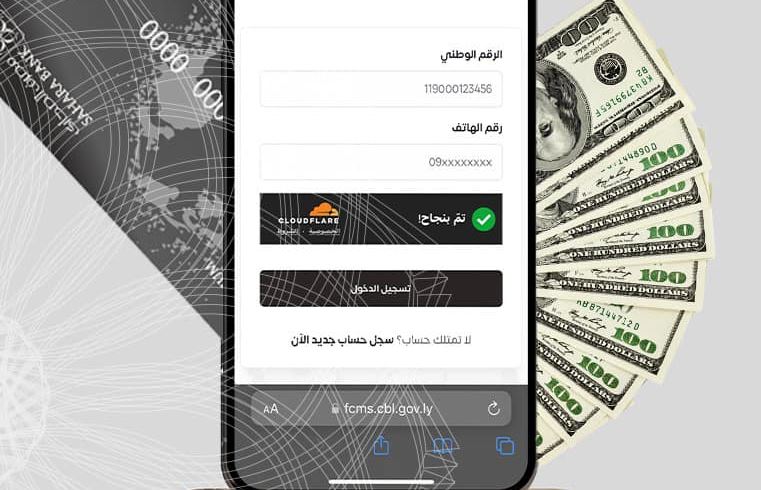

Depositors with less than one hundred thousand dollars in deposits, who constitute 85% of total accounts, will be able to recover them in full over a period of four years.

As for major depositors, they will be able to obtain one hundred thousand dollars, with the remaining portion of their deposits to be compensated through tradable bonds. These will be backed by assets of the central bank, whose portfolio includes approximately fifty billion dollars.

It was emphasized that the draft law includes “for the first time, accountability and auditing,” explaining that “anyone who transferred their money before the financial collapse in 2019, exploiting their position or influence, and anyone who benefited from excessive profits or bonuses will be subject to audit and will be required to pay compensation of up to thirty percent of these amounts.”

It was clarified that the law, which faces opposition from representatives of the banking sector on the grounds that it imposes heavy burdens on commercial banks, aims to “protect depositors and allow the recovery of their deposits.” It also aims for “the recovery of the banking sector through the evaluation of bank assets and their recapitalization so they can resume their natural role in financing the economy, stimulating growth, facilitating investment, and eliminating the widespread cash economy.”